The United States Doesn’t Have a Housing Crisis

It Has Three.

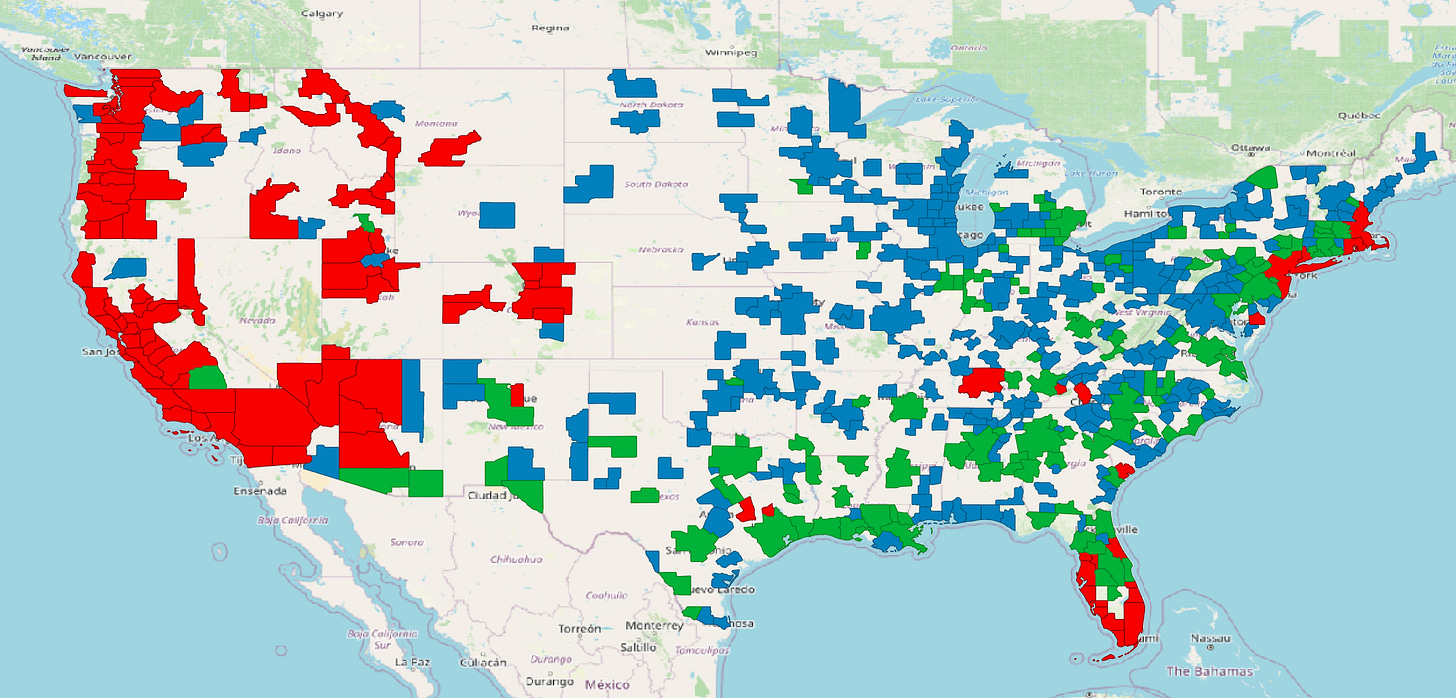

After a lot of hard work by activists, America’s political class has finally started to accept that we are in a housing crisis that is ruining everything. But what do we mean when we talk about a housing crisis? The reality is that housing market conditions are quite varied across the United States. There is not one single crisis, but three different varieties of housing crisis that require three different policy responses.

Housing Shortage Crisis: These are the places where there is simply too little housing, of every variety, everywhere in the city. In these places, we urgently need to build more housing, in any form.

Housing Inaccessibility Crisis: These are the places where housing is cheap by national standards, yet still inaccessible due to low local incomes. In these places, the near-term fix is to build subsidized deed-restricted affordable housing and expand access to housing choice vouchers. The long-term fix is to create the conditions for economic revitalization.

Housing Choice Crisis: These are the places where the typical family can afford a home, but they have little choice regarding the type, quality, or location of housing. In these places, we should focus on allowing a range of housing typologies in the most in-demand areas.

The Housing Shortage Crisis

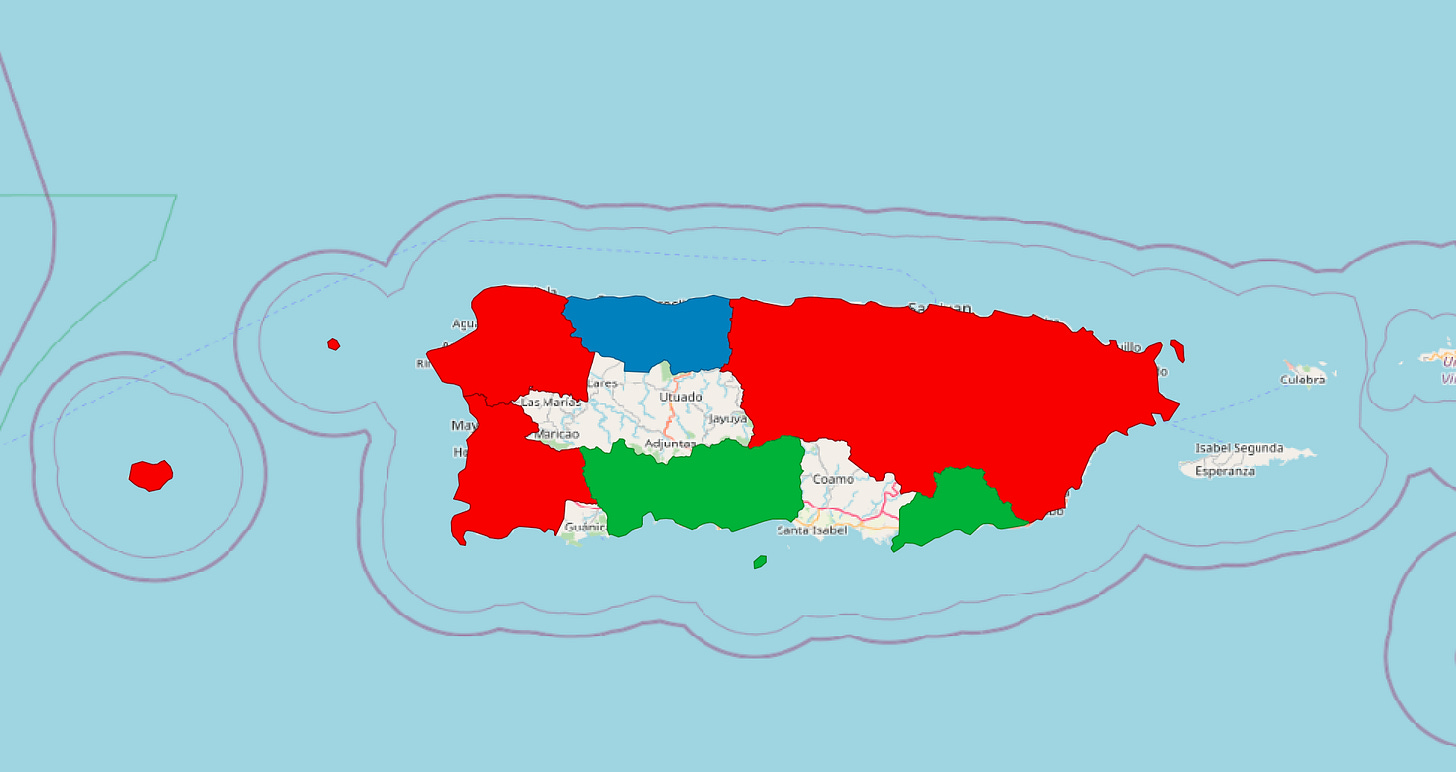

In 112 cities, there is a “classic” housing crisis—very simply, these cities need more housing. They are mostly concentrated in the Northeast, Mountain West, and along the West Coast. The entire state of Hawaii suffers from this variety of housing crisis.

In these cities, the typical family will struggle to afford a typical home. Making rent will likely be a source of some stress for most households. For my nerdier readers, I operationalize this as cities where the ratio of median home price to median household income exceeds five—an established upper bound of a healthy housing market.

These are the places where we need to build a lot more housing—there is no other way around it. Whether all this new housing takes the form of sprawl, infill, or some mixture of the two, I’ll let you all decide in the comments—whatever we go with, we need to build a lot more of it in these cities, and fast.

Some of these places (e.g. Colorado and Tennessee) are on the tail end of a building boom that will soon bring prices down. Some of these places (e.g. Montana and Oregon) have recently adopted reforms that should get them building. But those places where the housing shortage is most acute (e.g. California and Hawaii) are mostly not building, or even taking the bold steps needed to start building.

What’s Up With Florida? The Sunshine State is a place where a lot of wealthy people with low incomes go to spend the final years of their lives in expensive houses—hence they do poorly on any home price-household income ratio. Should Florida be building a lot more homes? Yes, almost certainly. But the situation likely isn’t quite as bad as this map would suggest.

The Housing Inaccessibility Crisis

In 123 cities, housing is cheap by national standards—indeed, much of the existing housing stock might be cheaper than the cost to build it today! Yet housing affordability remains inaccessible to many families owing to unusually low incomes. These are mostly in the Rust Belt and the South.

In these cities, if you have a decent job, you likely won’t have much trouble making rent or even buying a home. I operationalize this as cities where (a) over half of renters spend over a third of their income on rent and (b) over a quarter of renters spend over half of their income on rent, but (c) there are not otherwise signs of a classic housing shortage.

In these cities, incomes for many households are not high enough to comfortably cover the cost of even naturally occurring affordable housing. In the near term, policymakers should build subsidized housing, expand access to vouchers, and/or help families move to more prosperous places. In the long term, they should create the conditions for economic revitalization.

What’s Up With All the College Towns? The unfortunate thing about college students is that they are temporarily poor. They usually make do by finding roommates and settling for crummy housing. If you want to help them, you’re going to need to build dedicated student housing. I tend to think that college students are human beings deserving of shelter—a hot take with college town NIMBYs!

Housing Choice Crisis

In the remaining 295 cities, the typical family has a decent shot at someday owning their own home, and most renters spend a manageable share of their income on rent. But this affordability usually requires unnecessary trade-offs: In a Southern city, it may entail enduring a long commute to the edge of town. In a Midwestern city, it may mean settling for a neighborhood with poor public services or limited access to jobs.

In almost every city in America, arbitrary zoning rules make it hard to build housing in the most desirable places, including near jobs, shops, parks, transit, and schools. Within cities, discretionary reviews and high parking requirements often make it hard to build in the most desirable neighborhoods. And rules like single-family zoning and minimum lot sizes often make it impossible to build in high-opportunity suburbs.

Few cities today allow the range of housing typologies needed to support households at various income levels and stages of life. For most families, it’s “live in a detached single-family home in an auto-dependent neighborhood” or nothing. If prices are any indication, many Americans might prefer a townhouse or a condominium in a walkable neighborhood with restaurants, bars, and transit nearby—we simply don’t give them that option.

The focus for these cities should be on removing regulatory barriers to building a variety of housing types in all neighborhoods—especially in those areas with the greatest unmet demand.

What’s a Policymaker To Do?

The good news is that all of these solutions make sense everywhere. Indeed, we really need to be able to walk and chew gum on housing—every city should aim to remove barriers to sufficient housing production, particularly in the most in-demand areas, while also providing needed support at the bottom of the market. My argument here is mainly about how you should prioritize.

In Los Angeles, a housing shortage city, the focus must be on expanding the overall supply of housing. But we should focus our upzoning efforts on places where Angelenos most want to live, such as the jobs- and amenity-rich Westside. In the meantime, we need to line up the support for those families at the bottom of the market.

In Flint, a housing inaccessibility city, the near-term focus needs to be on economic recovery and affordable housing. But building lots of housing will help everyone, and when the bounce-back happens—as it inevitably will—the city will be glad to have already removed needless barriers to new housing, especially in high-opportunity areas. The example of Buffalo is instructive in this regard.

In Lexington, Kentucky, a housing choice city, the focus needs to be allowing for a range of housing types—including townhouses and small apartments—in desirable, close-in neighborhoods like Kenwick. But it must also remain mindful of increasing the overall housing supply commensurate to demand, while lining up support for low-income families as good jobs keep flowing into the region.

It’s trite but true: the first step to solving a problem is to correctly diagnose it.

Thanks Nolan. Maybe be careful with headlines like this: folks that just read headlines will think this justifies their denial.

Perhaps next time give it a “The United States doesn’t Have a Housing Crisis. It has three of them” or something

Great post.

But I'm going to push a little bit, Nolan.

Most of your "Housing Inaccessibility" cities are now also "Housing Shortage" cities.

The mortgage crackdown in 2008 hit hardest in cities where incomes tend to be lower. That decimated the single-family construction market in most of those cities. Prices collapsed because families were blocked from mortgages, but rents skyrocketed.

Just since 2015, rent (after adjusting for inflation!) in Atlanta, Orlando, and Charlotte are all up 30%-40%.

They look affordable if you just look at prices, because prices collapsed when mortgages were cut off. Rents have finally risen enough that the previously niche build-to-rent single-family segment is rising up to fill the gap. Those new houses will be built when the price of existing homes finally recovers enough to make building new homes economical, but the rents required to make that happen are MUCH higher than they used to be.

Going back to 20th century mortgage standards will be MUCH more helpful in those markets than rent subsidies, etc. will (though of course, there will always be a need for some of that).

The probability of banning the new rental markets appears to be higher than fixing mortgage access.

But, my more basic point is that most of those cities had moderate construction activity before 2008. Since then they have had construction activity and rent inflation more akin to the shortage cities. They are, unfortunately, shortage cities now.