Where Could the Federal Government Actually Build Freedom Cities?

And where should the BLM sell off land generally?

Over the past few years, Republicans have coalesced around the idea of selling off federal land. Historically, this issue was tied up with scuffles over ranching rights. Yet a mounting national housing shortage has given the idea new life as a way of unlocking land for housing. In 2023, Utah Senator Mike Lee introduced the HOUSES Act to do just that. Expect it to pass next year.

The federal government does own a lot of land. Nationally, around a third of all land in the US is owned by the federal government. Most of it is out West. In Nevada, the federal government owns 80.1 percent of all land. In California, it owns just under half. By contrast, the federal government owns less than 2 percent of most Midwestern and New England states. In Connecticut, it only owns 0.3 percent.

Much of this land serves a purpose: About a quarter of federal land is protected habitat and/or parks. A third is covered by national forests. And approximately 4 percent is owned by the Department of Defense. The largest federal landowner is the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). In many cases, this land is leased to ranchers. In some cases, it doubles as habitat or recreation land. But much of it sits altogether unused.

Opening up federal land was core to President-elect Donald Trump’s plan for housing. Yet he added an unusual spin, proposing that America build 10 “freedom cities” on federal land. Details are sparse, but it seems like Trump has in mind special economic zones that would enjoy lower taxes and more liberal regulations. The idea has been predictably polarizing.

Most of my fellow YIMBYs have been dismissive of the idea. I don’t blame them: Most federal land remains public land for the obvious reason that nobody wants to live there. The vast majority of BLM land is either in the middle of nowhere or carved up by mountains, far from the coastal epicenters of the US housing crisis.

But this belies the fact that the federal government really does own a lot of land well-suited to housing—and is uniquely positioned to build it, given its insulation from local zoning and complaining local NIMBYs. With an urbanist like North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum likely to be at the helm of the Department of the Interior—the agency that oversees BLM—next year, releasing federal land could potentially do a lot to bring housing prices under control.

As for where we could build entirely new freedom cities? Well, we’ll get to that.

Selling Off Federal Lands Isn’t Going To Help Most Cities…

Let’s start by setting expectations: Opening up federal lands isn’t going to help most US cities. East of the Rockies, virtually all federal land is either a military base, a national park, a national forest, or an American Indian reservation. Even on the West coast, high-cost cities like Los Angeles, Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle are far from BLM lands.

This isn’t to say that releasing federal lands won’t help any cities. In states like Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah—the five states that had the most extreme run-up in home prices over the past four years—most cities are hemmed in by federal land. Selling off close-in federal lands for housing development will help to bring prices down.

Though even out West, caveats are in order: While building more housing on the periphery will help with overall supply, it will mean more households living farther from job centers, universities, and daily necessities—and on the hook for higher transportation costs. If prices are any indication, the greatest unmet need for housing is for smaller homes closer to downtown.

Will building new subdivisions 10 miles outside of Reno help to bring down prices? Yes, almost certainly. But it would probably be more helpful to build a lot more townhouses and apartments closer in town. There really is no alternative to zoning liberalization.

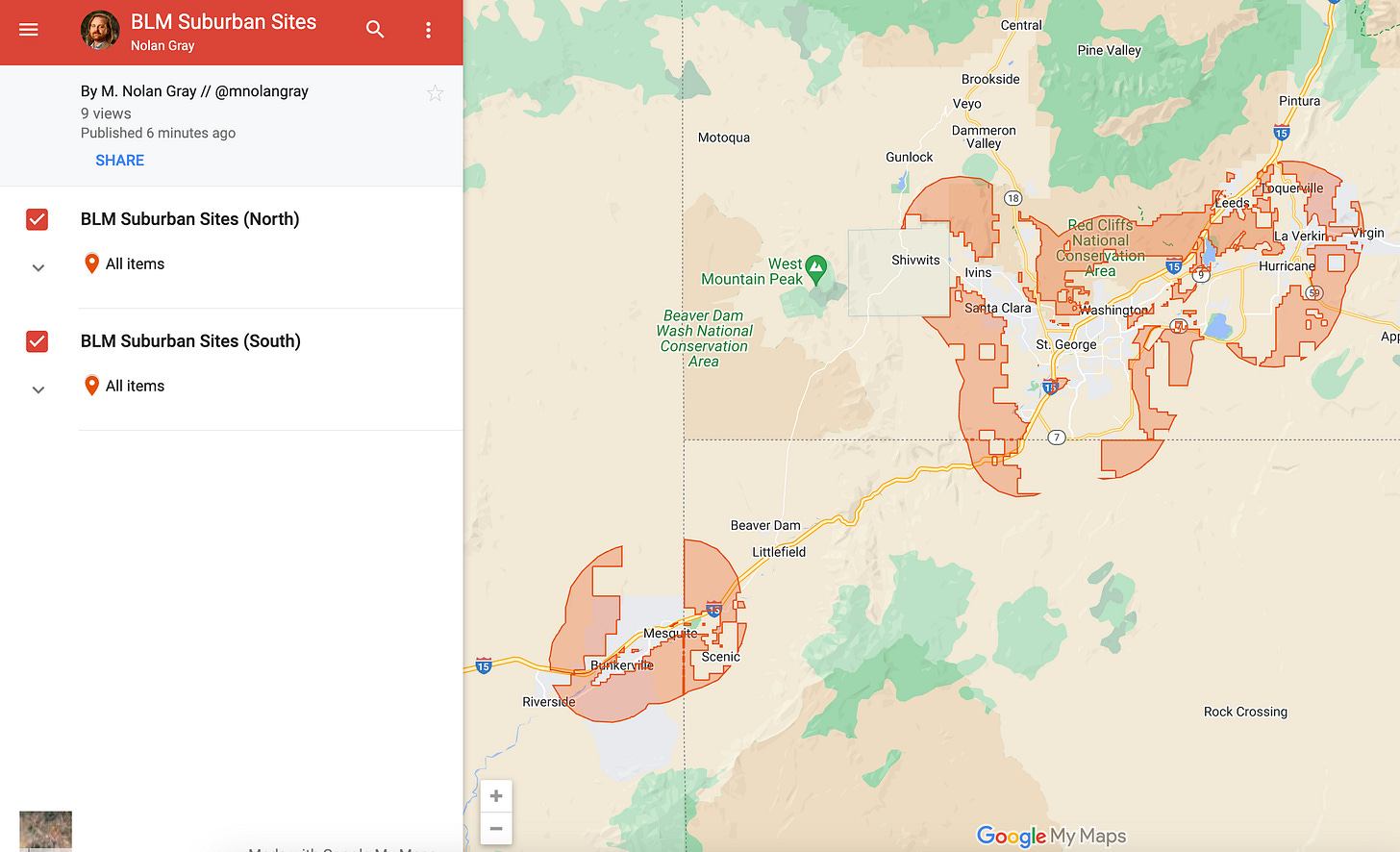

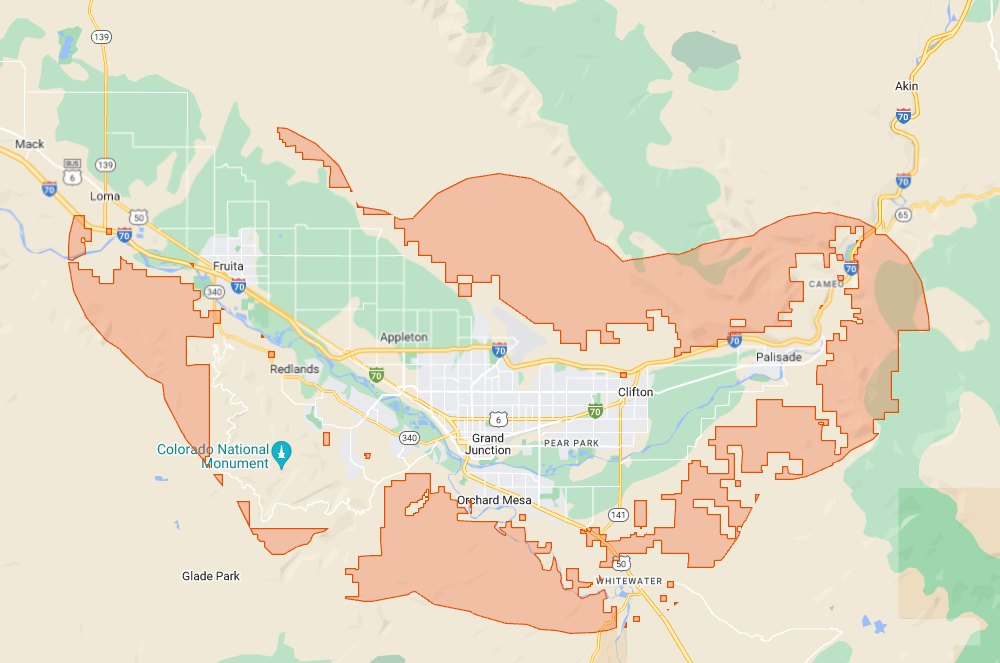

…But It Could Help In Some Western Cities

To find out where it might make sense for the federal government to make BLM land available for housing development, I decided to map it. The map below depicts BLM land that is either (a) in an existing urban area or (b) within five miles of an existing urban area—hence, the rounded edges. Click the image below for an interactive map.

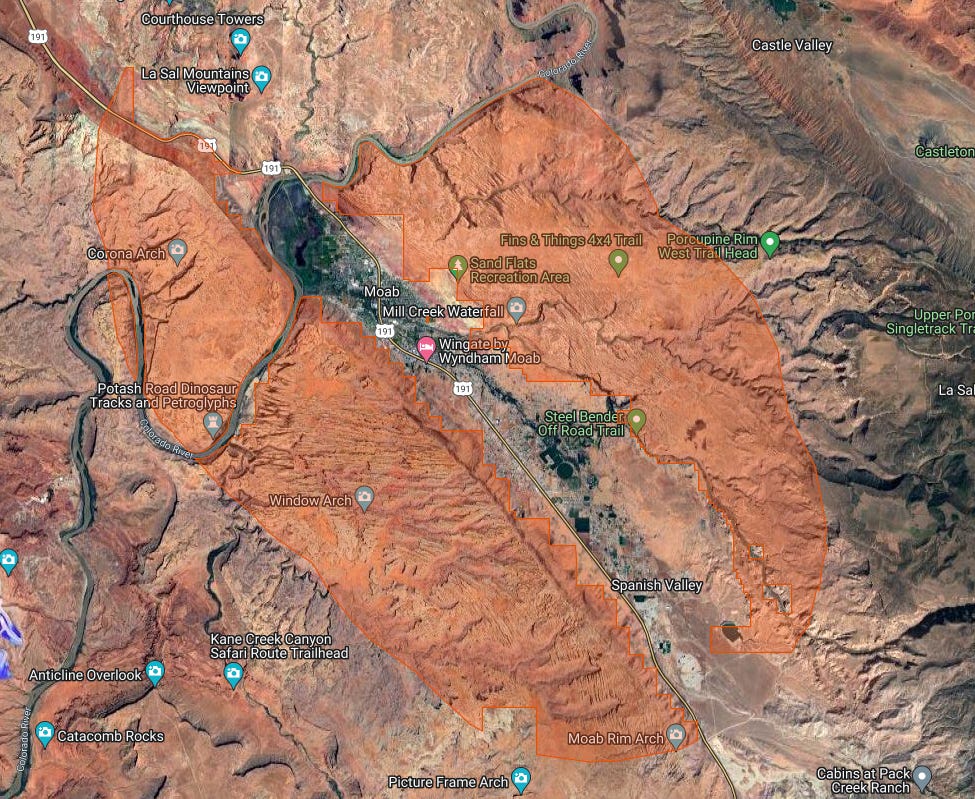

A lot of this land probably doesn’t make sense for development. In many cities, the BLM land just outside of urban areas constitutes a natural barrier to growth—as with the hills outside of Moab. Alternatively, BLM land often covers land of outstanding natural value, as with the Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area west of Las Vegas.

But at least some of this land should be up for conversation. In many Western cities, BLM land effectively acts as a kind of urban growth boundary. In cities like Grand Junction and Las Cruces—cities where home prices increased by approximately 50 percent between 2020 and 2024—federal ownership blocks housing on many hundreds of acres of close-in land of little natural or recreational value.

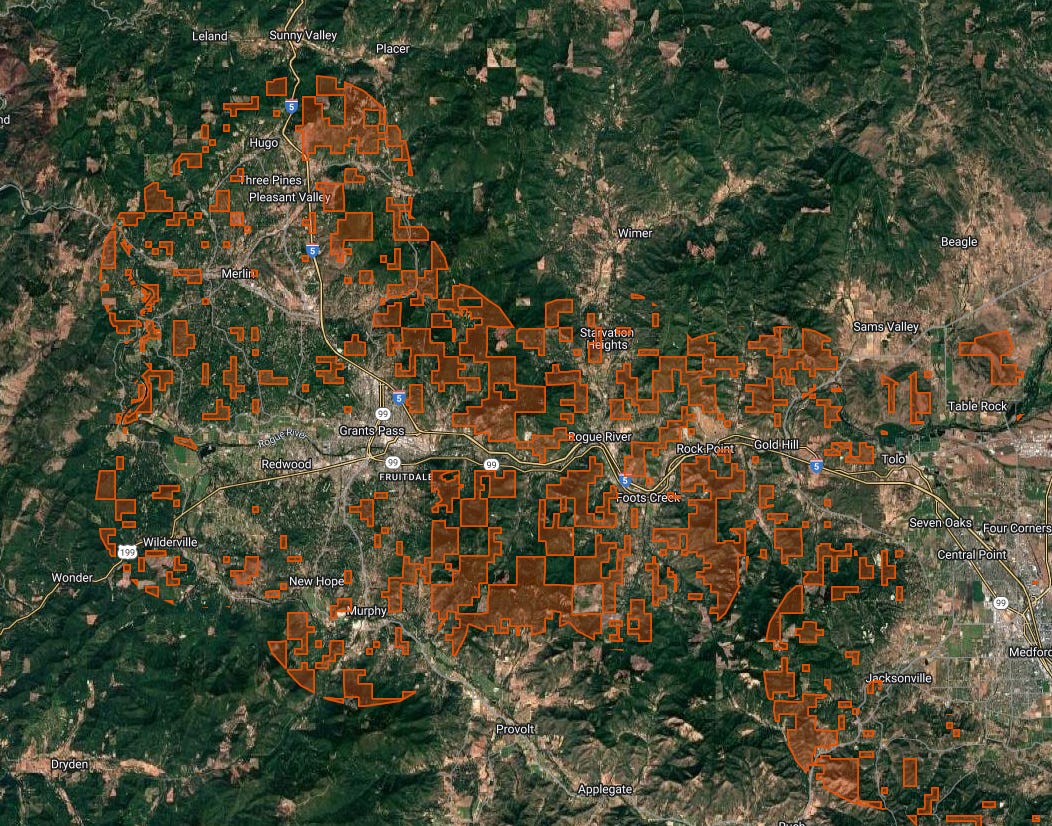

Maybe you like these de facto urban growth boundaries, so let’s set them aside. In many parts of the West, cities are ringed by a patchwork of BLM land that is the worst of both worlds: They take a lot of land offline without necessarily furthering any conservation or recreational goal. Consider the situation in Grants Pass, a city that made headlines for disliking people who can’t afford a home.

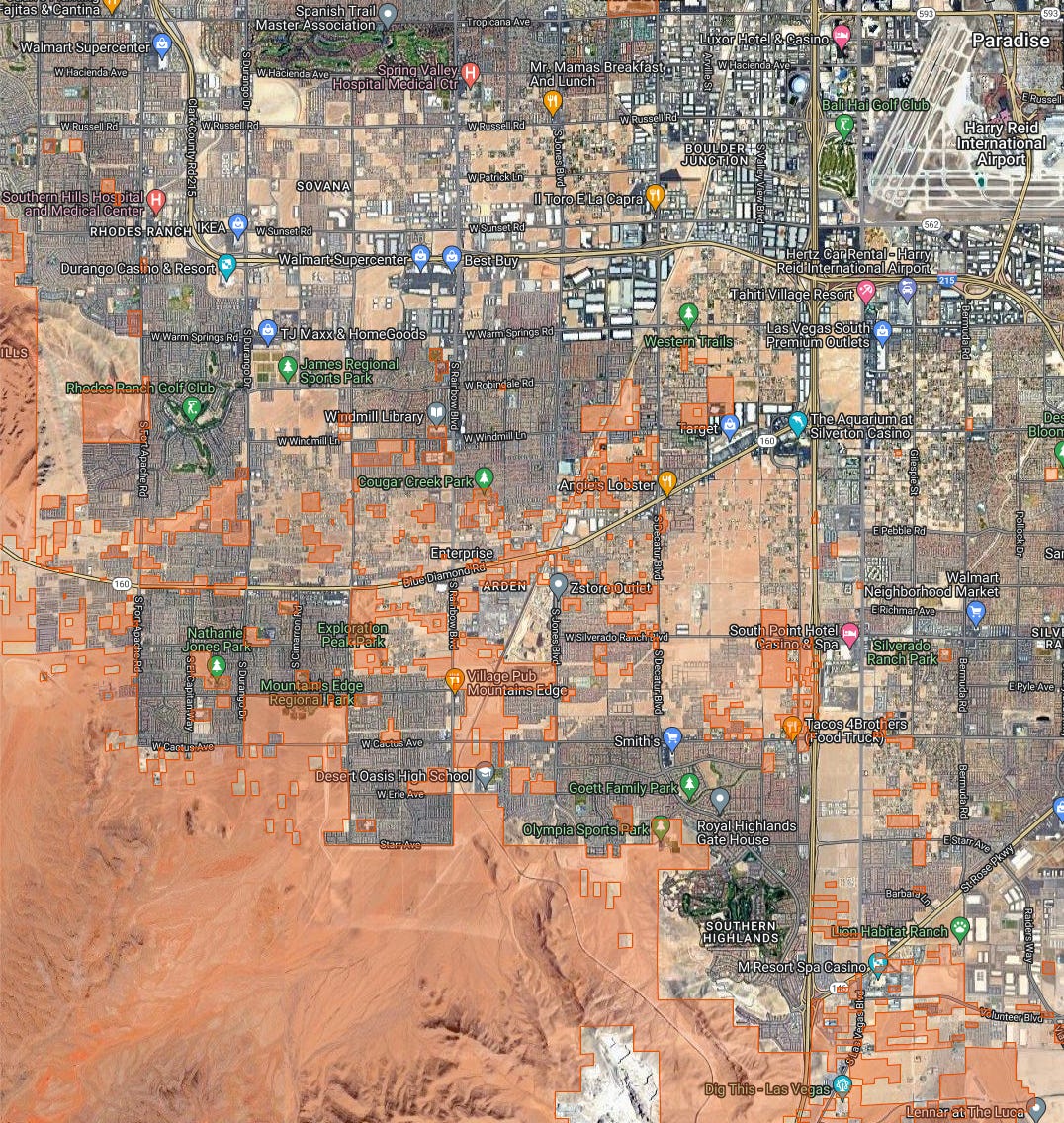

Maybe you even like this Swiss cheese variety of urban growth boundary. But a lot of BLM land is already completely enveloped by urbanized land. Consider Las Vegas: The city’s Southern edges—less than 15 minutes from one of the busiest airports in the world—are a chaotic quilt of BLM and private land that serves only to sprinkle litter-strewn empty lots amid what is now fully built-out suburbia.

If we sold off all of this land, it would only result in 0.05 percent reduction in the federal real estate empire. I don’t think we need to sell off all or even most of it. Much of this land just isn’t well-suited to housing. But releasing the small fraction of this land that is well-suited to future growth—and prioritizing walkable mixed-use development on a classic street grid—could help to improve affordability in these communities.

Enough of This Boring Stuff. Where Can We Build Freedom Cities?

The trouble with building new cities is that the best land is already taken. For the most part, all of the large flat sites near freeway and railroad junctions, harbors, and natural resources already have cities on them. At great cost, we can occasionally cheat these factors and build a city anyway—as with new political capitals. But for the most part, cities only form where there is an economic rationale.

Even if you can line up the capital needed to build new roads, sewers, and an airport, nobody is going to move there unless there are jobs. This is why Alain Bertaud—a former principal urban planner at the World Bank—is reflexively skeptical of the idea of new cities. If they can get off the ground at all, most new city projects end up like California City.

To hedge against this risk, Bertaud advises that new cities start on the periphery of existing metropolises. This deals with the two biggest challenges facing new cities: First, it avoids needing a brand new airport—the costliest part of building a modern new city. Second, it allows earlier residents to piggy-back off existing labor markets, universities, and consumption amenities.

Thus, new cities face a Goldilocks problem: Any new city will need to be far enough away from existing cities to have room to grow, while close enough for residents to commute to an existing city if need be—a variable that will heavily depend on what type of transportation infrastructure the government builds.

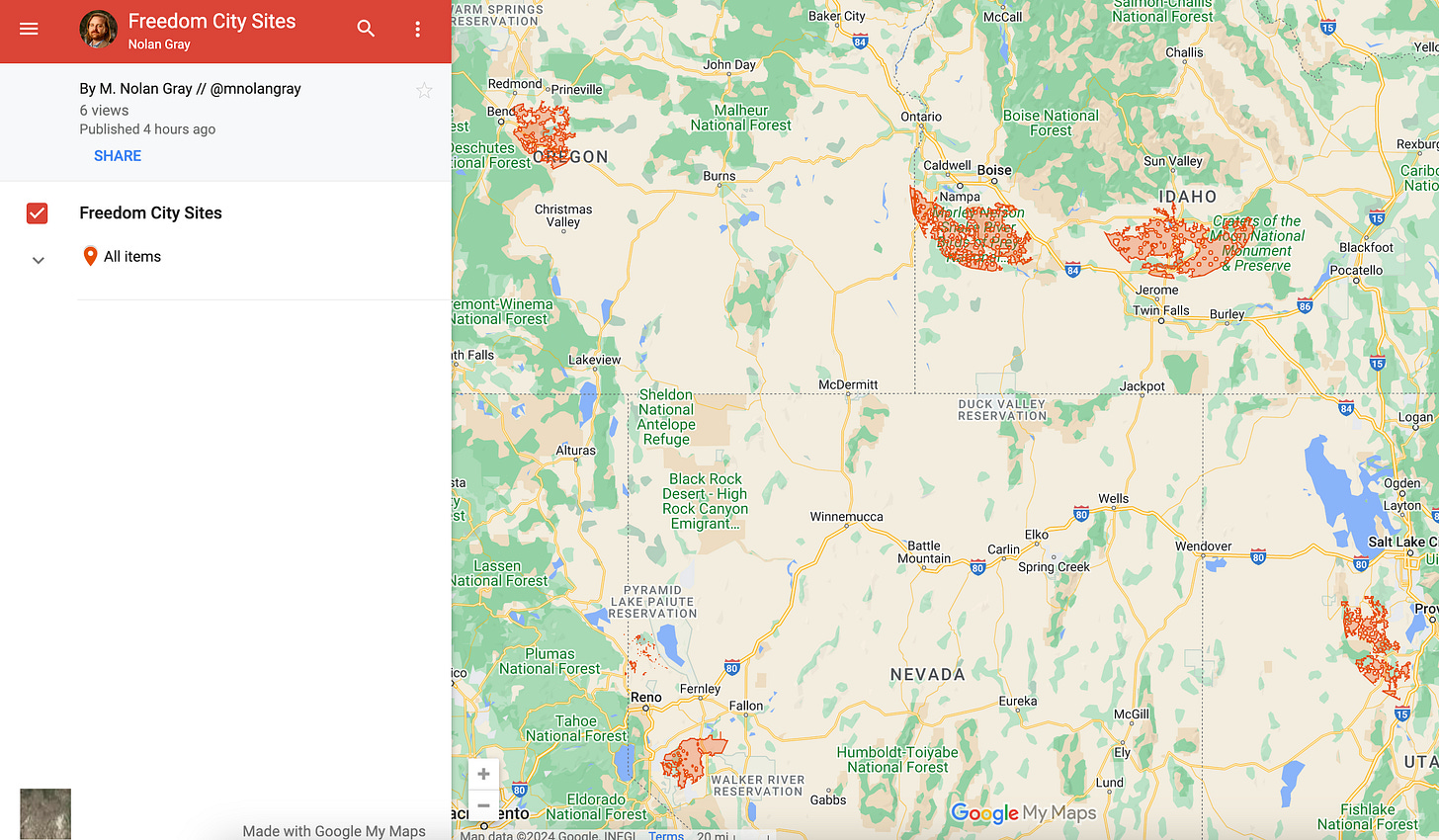

Here’s how I chose to operationalize Bertaudista thought and map eligible sites for any federal new city projects:

First, I removed any BLM land that is less than five miles from an urbanized area. These are better thought of as classic suburban additions.

Second, I removed any BLM land that was more than 60 miles away from an airport with at least 100,000 annual enplanements. This is my arbitrary cutoff for what qualifies as a minimally serviceable passenger airport.

Finally, I removed any parcels that were less than 100 square miles. This is my arbitrary cutoff for the minimum amount of land you would need for a new city.

A couple of methodological caveats before you rush to the comments section: Yes, these cutoffs are arbitrary. They nonetheless offer a starting point for identifying where we might site new cities. And no, this is not an exhaustive list of important criteria. A more comprehensive site suitability analysis should consider environmental factors, such as flooding and slopes. This was just a silly little weekend project—go easy on me.

It strikes me that there are at least five “freedom city” sites spread across the West. I have ranked them based on my superficial read of their relative viability, and given them each a cheeky name.

Utarado, Utah—Coltah-Colorado: At the Utah-Colorado border, Interstate 70 cuts through a largely uninhabited valley midway between Grand Junction and Arches National Park. A healthy tourism economy would arrive baked in, and social scientists would appreciate the creation of a new cross-state metropolis.

New California, Nevada: Like it or not, the Interstate 15 corridor connecting St. George to Los Angeles by way of Las Vegas is one of the fastest growing regions of the West. Don’t expect that to change any time soon. There are multiple federally-owned sites across the Arizona-Nevada-Utah tristate area that would be viable as new satellite cities.

Goodlands, Oregon: Just outside of Oregon’s fastest growing city—where the median home price just topped $725,000—the federal government owns 531 square miles of so-called badlands. If they can sort out the branding issues and build a train into town, the site could provide some relief to Bend.

Yimby, Idaho: Approximately an hour south of Idaho’s increasingly expensive Wood River Valley—home of Sun Valley—the federal government owns 1,295 square miles of mostly flat land. This region has seen some of the fastest home price appreciation in the nation over the past four years.

Carrizo, California: An hour inland from San Luis Obispo, the federal government owns approximately 335 square miles of undeveloped land. Much of this site is mountains and meadows best preserved as parks. But parts of it are flat and undistinguished. While remote, it’s the only site in high-cost California that would merit even a discussion.

Whichever sites the federal government chooses, it should prioritize three things: First, this is an opportunity to revive classic American traditions of city planning. That means sketching out a street grid and town squares. Second, the early focus must be on connecting these new cities to existing centers, meaning new roads and rail. Finally, the federal government will need to subsidize the arrival of jobs. This is going to be harder than it sounds.

If You’re Up For It, I’ve Got More…

So far, this post has narrowly considered how we might release BLM land. But what if the federal government pulled all of the available levers to end the housing crisis? When it comes to opening up land for new development, it’s about quality, not quantity—small amounts of land carved away from otherwise valid public uses could go a long way. Here are a few examples.

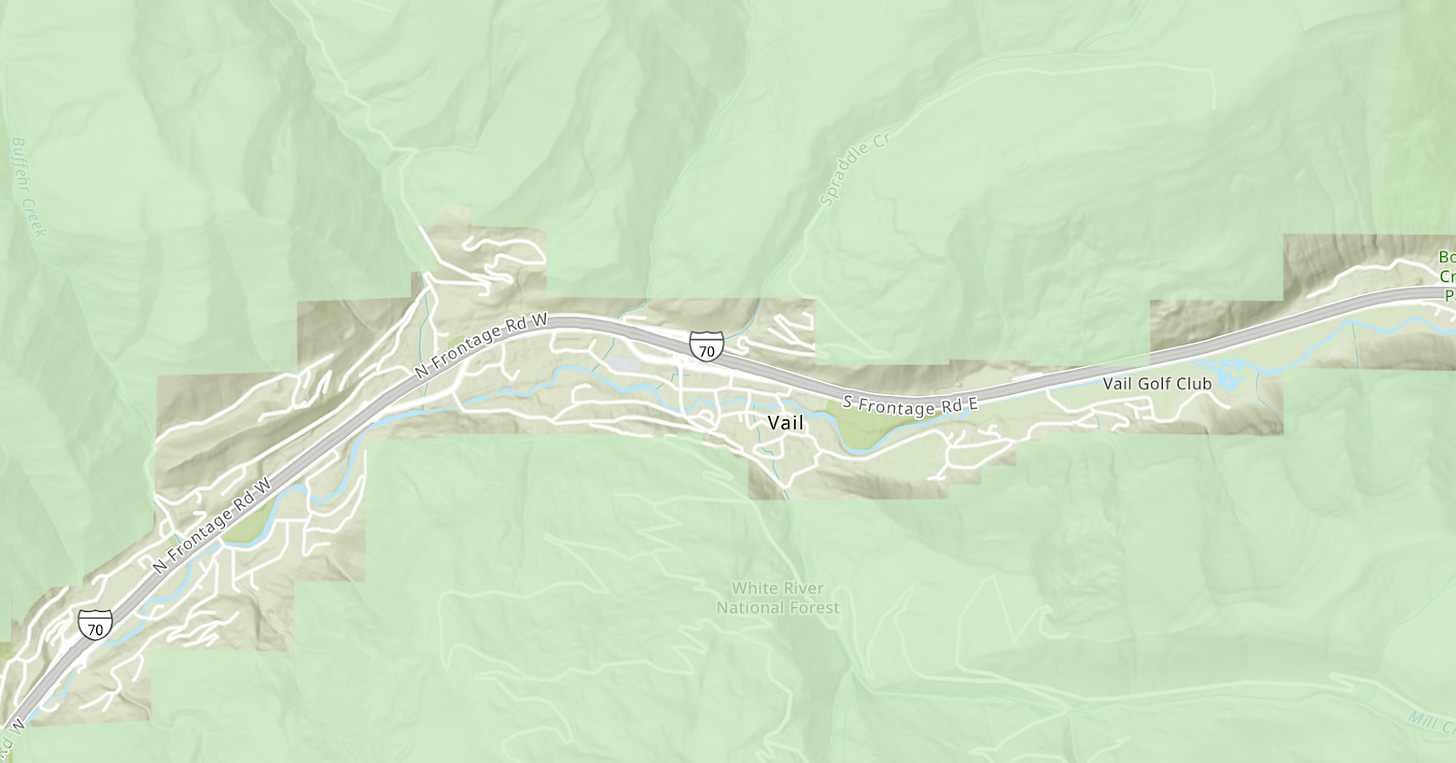

Building workforce housing in Mountain West resort towns: The most acute housing shortages in the country can be found in resort towns like Aspen, Jackson, Lake Tahoe, and Vail, where NIMBYs have made it impossible to build workforce housing. (These towns vote overwhelmingly blue, by the way.) These cities are all surrounded by National Forests. The United States Department of Agriculture—which oversees National Forests—should allocate small amounts of land at the edge of forests for workforce housing.

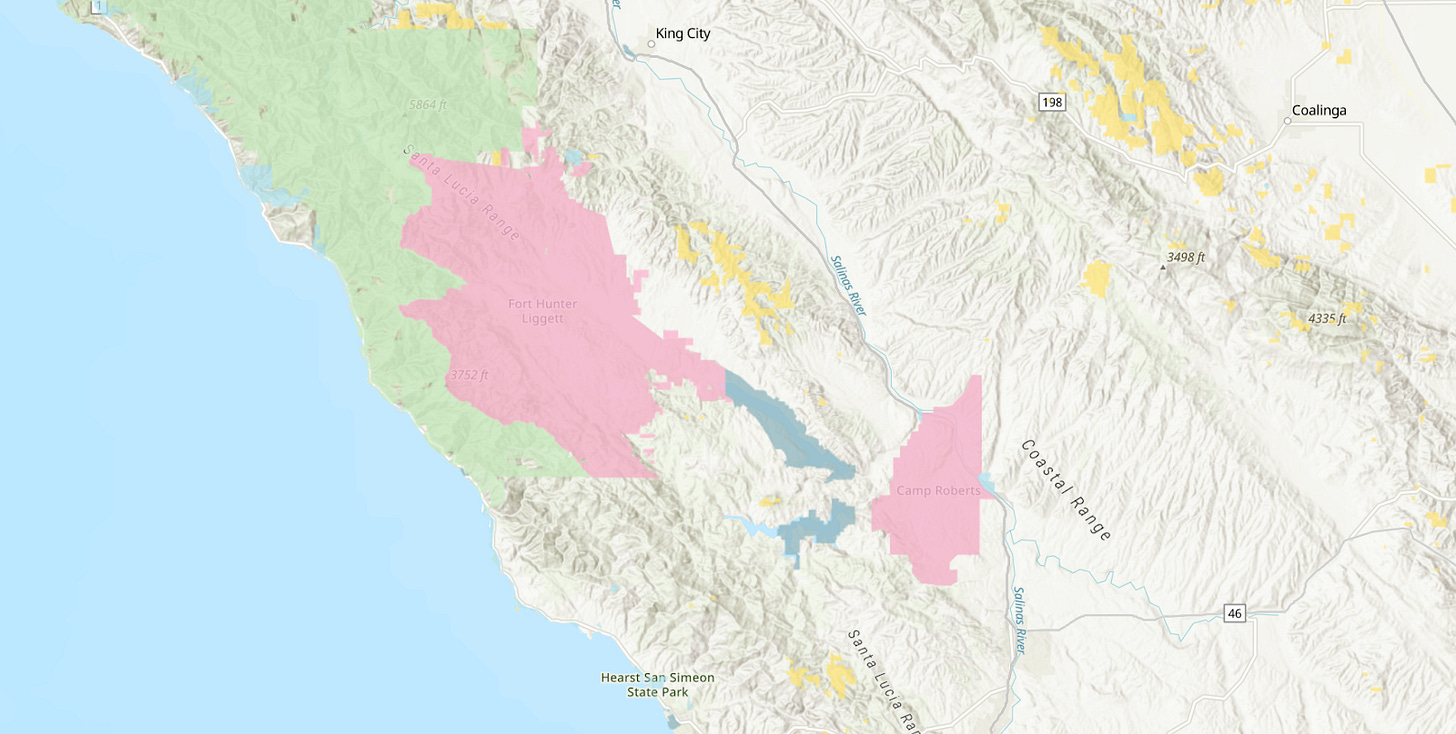

Open up surplus Department of Defense land in California: The Central Coast of California is one of the most expensive parts of the country. The Department of Defense owns two massive sites in this region: Fort Hunter Ligget and Vandenberg Space Force Base. The former is largely disused. The latter is the home of the newly-minted Space Force—and hub of a burgeoning space industry. Both bases should release excess land for needed housing.

Direct the USPS to leverage its real estate empire: The US Postal Service is one of the largest urban landowners in the country. From Manhattan to Waikiki, it owns prime real estate that is usually underbuilt. Congress should clarify that the USPS is exempt from local zoning and direct it to start building housing above its retail facilities. Nick Zaiac and I first proposed this back in 2020, and the Biden administration launched a pilot in 2024. The new administration should pick up the baton.

No airport closures without housing: Across the country, small airports are closing. Airport closures in places like Austin and Denver have historically been a valuable source of land for infill housing. Yet in places like high-cost Santa Monica, NIMBYs are fighting to block housing on the site of the soon-to-be-shuttered Santa Monica Airport. This should not be tolerated. The Federal Aviation Administration should condition the closure of any urban airport on a binding agreement to build housing on the site.

It’s Free Real Estate

An annoying quirk of politicians is that they will declare something a “crisis,” and then proceed to act like we are not in a crisis. How many mayors have proclaimed a housing crisis only to turn around and convene a study group? If we are in a crisis, we should take extraordinary measures to end it—that means an “all of the above” approach. Healthy cities need to grow up and out.

But there’s a reason why politicians walk back “crisis” claims: The US housing crisis persists because it has many constituencies. It’s easy to float the idea of releasing land in theory. But once specific parcels are identified, opposition will form. Once enemies, ranchers and environmentalists will lock arms, and homeowners on the periphery will defend their right to live in the last subdivision ever built.

The federal government is about to get a crash course in NIMBYism. It won’t be able to convince the person yelling at the Tuesday morning public hearing. But it might be able to win over normal people. Near existing cities, lands with even a whiff of conservation or recreation value should be kept public. (Or better yet, improved.) New additions should be well-planned. That means communities with a mixture of housing options, walkable street grids, neighborhood-serving retail, and parks.

It won’t be easy. But every city was once a new city.

"... or a Native American reservation."

Obviously they would have to be native-led - but are the reservations not, as one might put it - open for development, treaty port style? I've read in passing that the First Nations have been pro-development in some of the parts of Canada whether they have land.

The land around Las Vegas is already covered by a land sale program under the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act created by Harry Reid. It uses the proceeds from the lad sales for conservation. A good model. It’s allowed Las Vegas to continue to grow. https://www.blm.gov/programs/lands-and-realty/regional-information/nevada/snplma