Emergent Guatemala City

A dispatch from North America’s most rapidly changing city.

For the past nine years, Guatemala City has come to be my second home. Happily, the city is a natural paradise: A tropical valley at a high elevation, it enjoys perfect year-round weather. Magenta bougainvilleas billow over barbed-wire fences; lavender jacaranda trees fan out over cracked sidewalks. On a clear day, you can see four volcanoes from nearly anywhere in the city—at once, terrifying and awe-inspiring.

On my first few visits to Guatemala, I was startled by the poverty and inequality—mainly in rural areas. President Lyndon B. Johnson launched the war on poverty on the front porch of reasonably close kin in Eastern Kentucky, so I thought I had a handle on these issues. In retrospect, I was naive. Spending time around absolute poverty and extreme inequality has a way of sharpening your thinking about the nature of wealth.

Yet for all the negative things that have been said about Guatemala, it’s a place that is steadily improving.1 Over the past decade, GDP per capita has grown by nearly 20 percent—not the catch-up growth of the Dominican Republic, but hardly the stagnation of Nicaragua.2 Estimates vary, but by one measure, the average resident of Greater Guatemala City—there are probably between three and five million of them—earns roughly $20,000, in the range of a middle-income country.

You don’t need imputed statistics to notice Guatemala City’s rising middle class. On a monthly clip, new shopping malls open up, quickly filling with national and international chains. Ads increasingly appear in English, or invite upwardly mobile viewers to learn English. In 2023, the country opened its hundredth McDonald’s location. What clearer sign of middle-class ascendancy could you ask for?3

International commentaries on the urbanism of Guatemala City fixate on the exotic symptoms of informality: the ravine slums, the street vending, the unpermitted second stories, etc.4 I’m hardly innocent. On my second visit, my wife—a local ever willing to humor me—and I wrote a paper on informal parking markets in Zone 4. But the more time I spend in Guatemala City, the more I’m fascinated by all the formal development underway.

Across the city, hundreds of new condominium buildings have been built over the past decade, providing a wave of first-generation young professionals with “luxury” amenities.5 Consistent with basic economics, the building boom has been most prolific in those parts of the city where Guatemalans would most like to live. In Zone 10, a posh, centrally-located neighborhood that’s home to various hotels, new residential towers are going up at a steady clip.6

Historically, these developments were designed with a siege mentality, with blank walls, guard kiosks, and gated vehicular access. A 36-year civil war—and one of the highest violent crime rates in the world—will do that to your urban design. The result was the worst of both worlds: density without urbanism. But the war is over, and crime is slowly falling. New residential buildings now often have a street-facing lobby. Increasingly, they even have ground-floor storefronts, including cafes and salons.7

My wife’s family lives in well-to-do Zone 15. At the turn of the millennium, it was a neighborhood of tony single-family homes on quarter-acre lots. When I first started visiting, her mother lived in one of the first new high-rise buildings in the neighborhood. Today, there are over 60 similar nearby buildings in the development pipeline.

This sort of transformation would be unthinkable in the U.S., where our most affluent neighborhoods are closed off to new housing. But it wasn’t always this way: Before the rise of zoning, it was common for desirable North American neighborhoods to follow this path. Guatemala City’s Bel Air is simply maturing in Guatemala City’s Upper East Side.

In my position as the precocious outsider, I often ask locals what they think of all this change. They’re usually confused by the premise of the question. Unlike Americans, Guatemalans haven’t been habituated by decades of NIMBYism to feel they must have a take on every new development—let alone the right to block it. When a proposed high-rise risked blocking the views of an existing Zone 15 building, the residents didn’t call city hall. Rather, they paid the developer to build a shorter building.8

This isn’t to imply that there is no land-use planning in Guatemala City. In 2008, the city adopted the Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial (POT) with a goal of regularizing density.9 It followed Western land-use planning dogma, concentrating density along corridors, with a transect gradient extending outward.10 With little in the way of vehicle regulations, Guatemala City’s major corridors are noisy, smoggy, and generally unsafe. People want to live near corridors, but not on them. Thankfully, this policy seems to have been advisory in practice.

Locals are only reliably concerned about new development to the extent that it contributes to traffic. In this regard, Guatemala City feels familiar to this recovering Angeleno. Traffic comes up in literally every conversation. It dictates when you can leave your house and where you can go. It determines your hobbies, your friends, and your employment options.11 The city feels like it’s at breaking point—yet as it continues to grow, and more newly-minted middle class families buy cars, the traffic is only going to get worse.

🇬🇹🇬🇹🇬🇹

There’s a bertaudism I think about a lot. It goes something like this: Here in the U.S., planners have their priorities flipped. We rigidly micromanage the private realm, controlling what can and can’t be built on any given lot, while having little in the way of a plan for the public realm we theoretically control—that is, the optimal design and organization of streets and public spaces.

Los Angeles is the prototypical case: If you try to build on a private lot in the city, every aspect of the development—use, height, number of units, materials, parking—will be strictly prescribed. But leave your house, and you will encounter a chaotic public realm with little enforcement of nuisance behavior, bicycle and bus lanes that senselessly stop and start, and parking and traffic woes that could easily be solved with prices.

The inverse of Los Angeles is Tokyo: There, property owners enjoy a degree of freedom that would be imaginable in the Land of the Free. Within wide bounds, you can build whatever you like, and use the resulting space however you like. Meanwhile, the public realm is characterized by carefully maintained parks, streets that are optimized around a range of users, and safe, frequent, and reliable transit.

And then there’s Guatemala City: As a rapidly changing skyline suggests, the rules controlling private land are relatively liberal. The private realm is learning to a degree that would be unthinkable in the U.S. Amid a surging population and rising incomes, condominium towers are popping up next to posh single-family homes; new bodegas and cafés open up in old garages; floors spontaneously appear up on top of old homes in older neighborhoods.

But leave your home or office, and you’ll find yourself sitting in some of the worst traffic in the world. There are push and pull factors at play: Poor public transit, few multimodal lanes, busted sidewalks, reckless drivers, poor air quality, and the risk of violent crime make navigating the public realm in anything other than a car unspeakably unpleasant. Meanwhile, all of this new wealth puts cars within reach of more households.

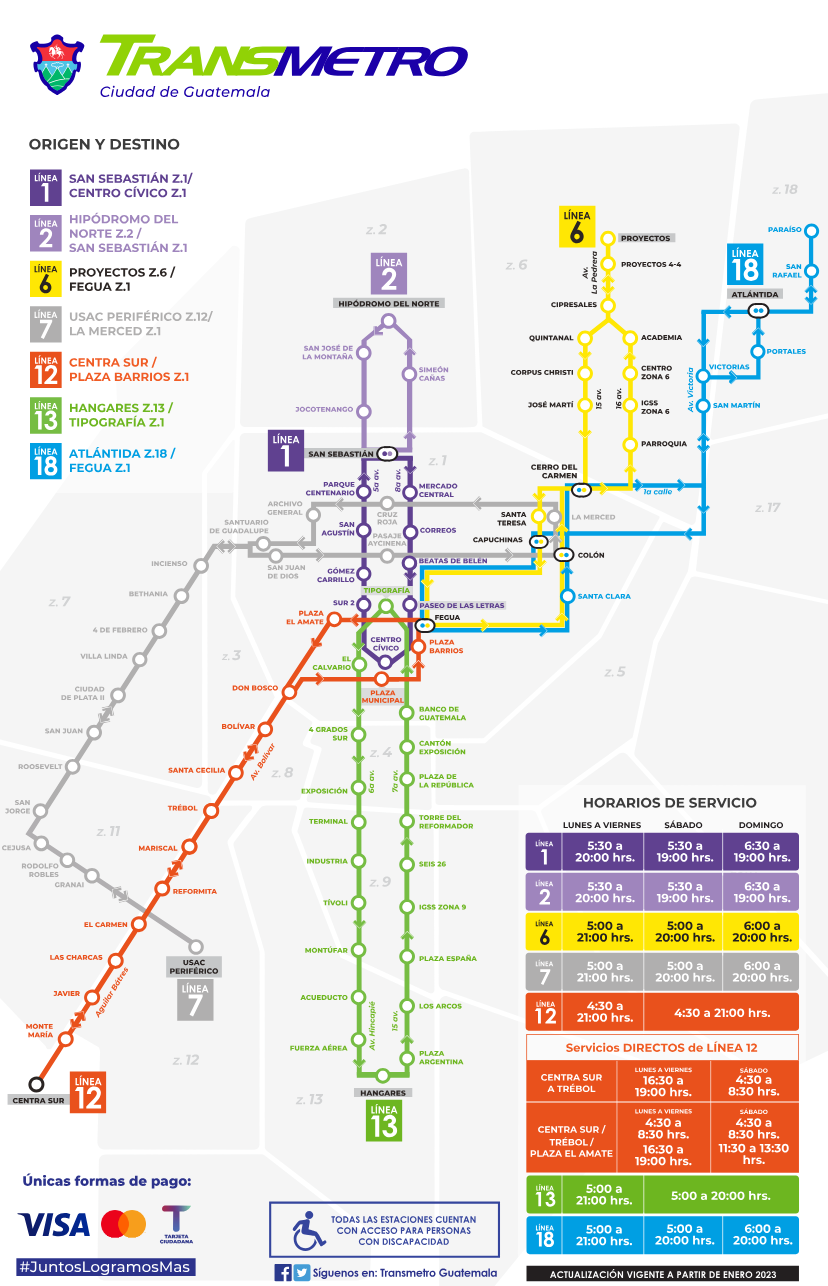

It may not always be this way: In recent years, the city has massively built out Transmetro, a bus rapid transit network stitching together the city. An enormously popular Pasos y Pedales is helping to normalize the idea that streets might be used for something other than vehicular throughput. And in 2027, the first urban rail line is expected to connect Greater Guatemala’s southern and northern suburbs by way of downtown.

Even so, jurisdictions across the region continue to build vehicular overpasses and underpasses, undermining any form of transport that isn’t a private automobile. The pace of pedestrian overpass construction seems to have slowed. But one suburb recently spent a few hundred thousand dollars on a billboard that reports traffic delays—an even more ridiculous expenditure to undertake in an age of smartphones. Needless to say, none of this meaningfully improves mobility.

As with many American cities, metropolitan Guatemala City is fragmented across at least 13 separate jurisdictions. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: there is minimal coordination in terms of transportation or land use.12 With any luck, Guatemala City will follow the lead of Île-de-France, and amalgamate into the Department of Guatemala—the state that approximately covers the entire metropolis.

The good news is that Guatemala City planners aren’t flying blind. Over the past 70 years, East Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan seem to have solved the problem of how to plan a booming metropolis. Perhaps the first step is to stop listening to all the American planners.

Well, with one exception.

For nearly 30 years, the country has been a reasonably stable republic, with regular transfers of power across party lines. Yes, elections are occasionally contested and chaotic—but who among us is without sin?

One of the ways you know things are improving is that things are improving is that high society Guatemalans now often complain that it’s difficult to hire maids or nannies. The women who would have done this work 20 years ago now have much better opportunities in call centers or textile factories. To my mind, that’s a fine problem for a country to have.

The Guatemalan McDonald’s is a fascinating topic in its own right. Guatemala was host to some of the first international locations, headed by an early female franchisee. These locations were the first to start selling smaller meals catered to children, with a free toy included—the genesis of what would later become the Happy Meal.

The notable exception is the “new town” Cayalá, a master-planned Spanish Colonial community that has somehow managed to incite the most spectacularly polarizing assessments, both domestically and abroad. For many observers, it’s a procedural tale about inequality. To my mind, it's a fine enough vision of one path Guatemala City might take. The city is going to have to build many thousands of neighborhoods in the coming decades—it would be far better for them to look like this, than the conventional gated, car-oriented status quo. Contrary to the hysteria, Cayalá is not a gated community, as with so much of the country. On a typical day, you will find Guatemalans of all incomes milling around.

Historically, the norm in Guatemala—as in many Hispanic countries—was for young adults to continue living with their parents until they were married. As I understand, this was due to both a laudable focus on family life, and a general lack of wealth. As Guatemalans become wealthier, and adopt U.S. cultural norms, this mode of living is fading away.

For the most part, neighborhoods in Guatemala city are inelegantly known as “zones,” the city’s formal subunits.

As I understand, city officials provide additional FAR such for amenities. I’m usually skeptical of such mandates in the U.S. But in Guatemala, where street crime is the overwhelming quality of life concern, I can sympathize. The eyes on the street created by glass lobbies and storefronts have a way of kickstarting a virtuous cycle for public safety.

When you can coax out an opinion, reactions usually seem to be a vaguely positive “I hope it has a shop on the ground floor” or a vaguely negative “It’s going to cause more traffic.” In a few cases, locals seemed to like the new development as a sign of Guatemala City’s solidifying status as the capital of Central America. In other cases, I heard familiar conspiracy theories about how all the units are sitting empty. To the American NIMBY, unwanted new development is always a tax write off; to the rare Guatemala NIMBY, unwanted new development is a money laundering scheme.

As in any city, planning in Guatemala City is in flux. This plan has since been substantially amended.

Unlike with classic transect thinking, POT’s density gradient largely ignores the traditional downtown. I have been told that this is because much of Zone 1 is made off-limits to infill development by various historic preservation policies. With the city’s most central neighborhood off limits, new development has shifted to gentrifying neighborhoods like Zone 3 and Zone 4.

How’s that for the “freedom” of a car?

As urbanization blurs these 13 jurisdictions, lingering ambiguities in jurisdictional boundaries have led to regular confusion over which jurisdictions are entitled to which property taxes. In one recent case, a major employer opening up shop right at the boundaries of Guatemala City led to a wholly unnecessary tax tussle with neighboring Santa Catarina Pinula.

Thank you for this wonderful essay. So insightful. I visited GC when I was young (visiting my adopted sister’s foster family), and it was, as you say, chaotic, beautiful, and smoggy in all the best ways. Those volcanoes are something else. Now I feel like I need to go back!

Love this!