Everything You Need To Know About SB 79

…but were too afraid to read about in the actual bill.

On October 10, 2025, Governor Gavin Newsom signed SB 79 into law. With the passage of time, this will be recognized as one of the most important pieces of legislation in modern California history. It marks the fulfillment of at least eight years of work, beginning when Senator Scott Wiener first introduced SB 827, and signals the end of the first phase of YIMBYism—a theme this blog will return to in a future post.

Throughout the process, SB 79 has been shrouded in a fog of misinformation. And this is only the beginning: In a little over eight months, the law will take partial effect. We expect cities to spend years adopting and refining local alternative implementation plans. Beginning around 2030—with the start of the seventh Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) cycle—the law will take full effect.

Given that developing and passing this bill has been the focus of our lives over the past year—along with Senator Wiener’s staff, some amazing co-sponsors, and the whole California YIMBY team—we would like to take a moment to go deep into the weeds. In this first post, we will clarify exactly what SB 79 does as policy. If anything is unclear (or if you think we got something wrong) let us know in the comments.

In future posts, we will shed some light on how we passed it and where the YIMBY movement goes from here.

TL; DR.

SB 79 allows mid-rise multifamily housing within a quarter to half-mile of subway, light rail, and bus rapid transit (BRT) stations across California, as well as the busiest commuter rail stations.

Elements of the law will phase in, and cities can adopt an Eckhouse Plan—an alternative implementation plan to move around (but not reduce) allowed densities.

The bill also empowers transit authorities to establish the applicable development standards on parcels they own.

Where does SB 79 upzone?

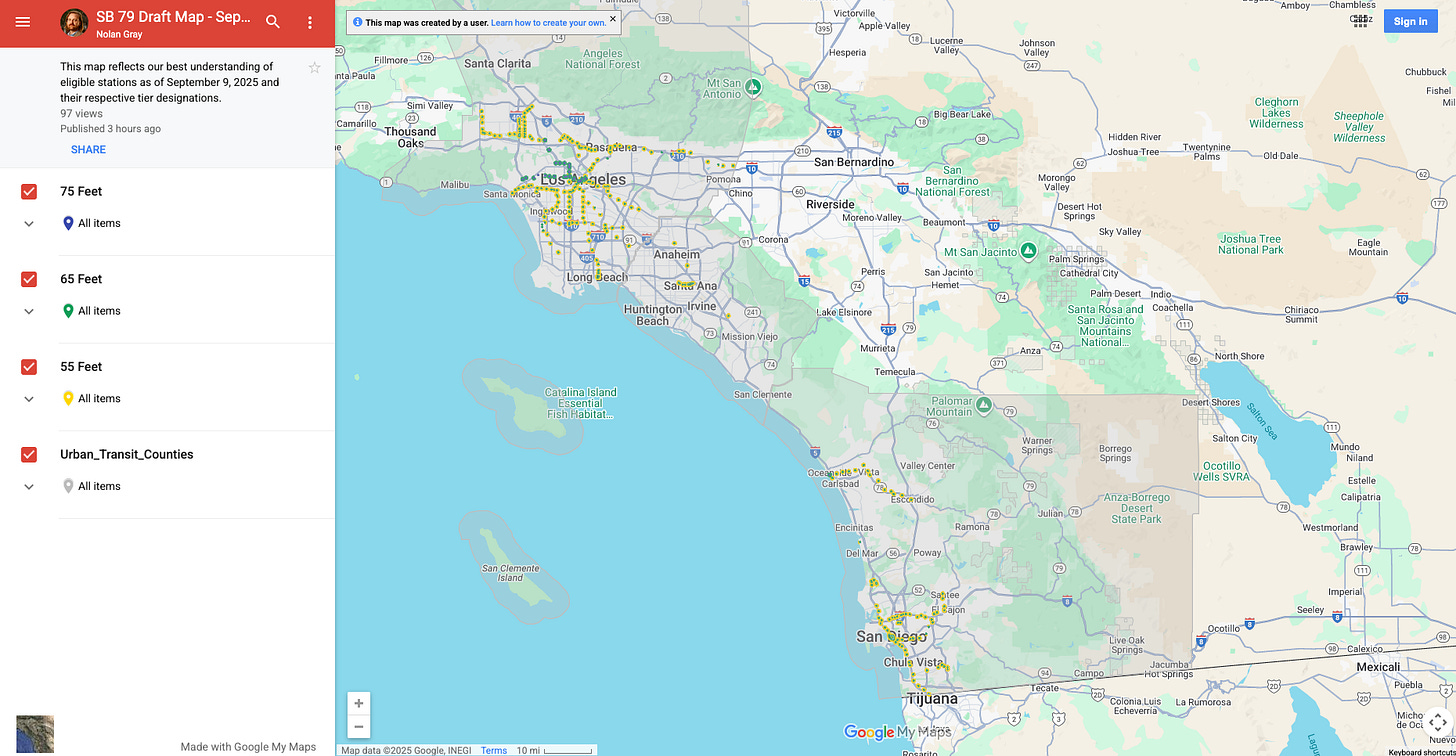

The bill only applies in urban transit counties. These are counties with 15 or more passenger rail stations. This includes the counties of Alameda, Los Angeles, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara.

🤓☝️ Ahem! Orange County will be covered when the streetcar opens next year.

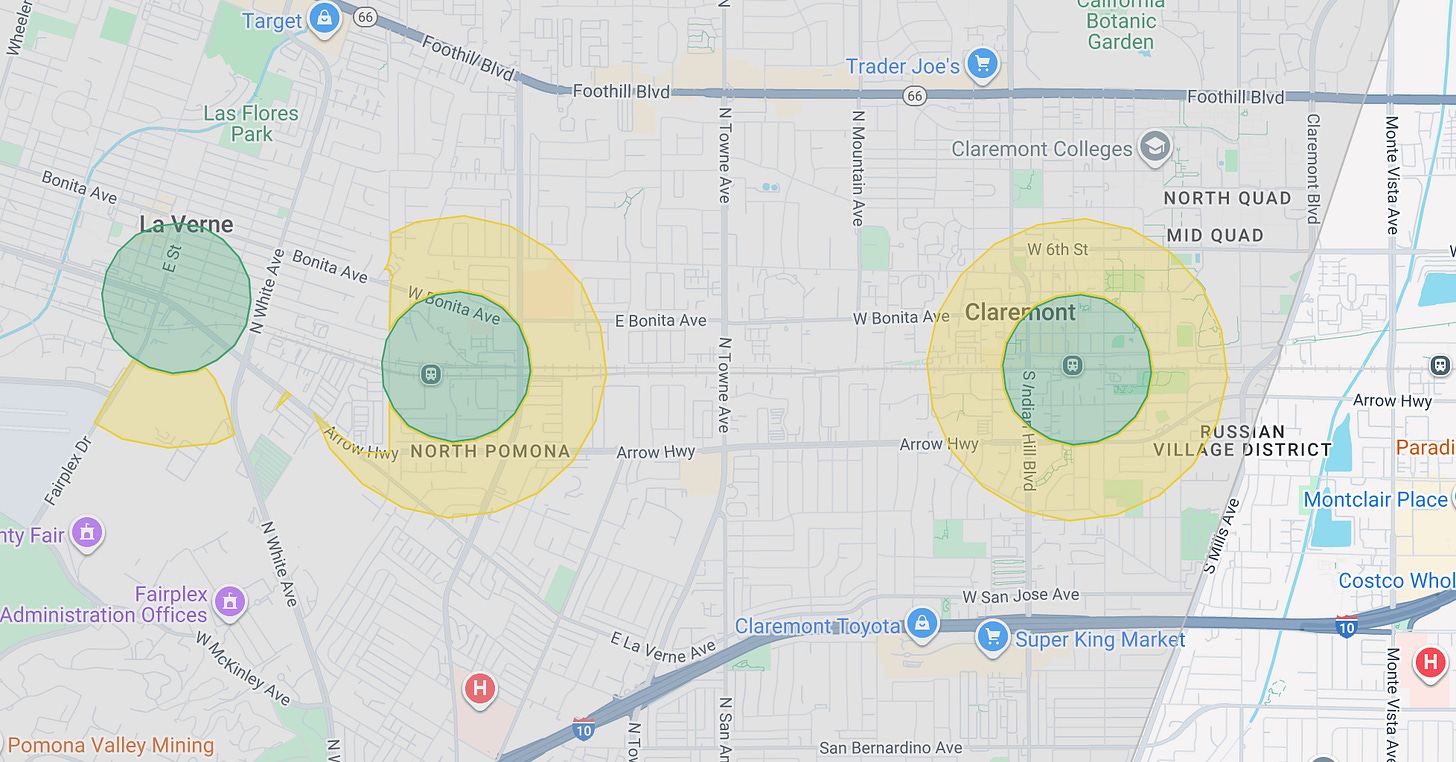

Within these counties, areas within a half-mile of most of the following stations are now designated as transit-oriented development (TOD) zones:

Areas within a half-mile of all heavy rail (e.g., BART) and/or very high-frequency commuter rail stations—defined as stations that run 72 or more trains per day—are designated as Tier 1 TOD zones.1

Areas within a half-mile of all light rail (e.g., the San Diego Trolley), BRT, and/or high-frequency commuter rail stations—defined as stations that run 48 or more trains per day—are designated as Tier 2 TOD zones.

🤓☝️ Ahem! The definition of BRT is pretty strict. It’s not your neighborhood bus stop. To qualify, a bus line must have (a) a full-time dedicated bus lane and (b) peak headways of 15 minutes or less. (In plain English: “headway” is how frequently the bus comes.)

In smaller cities, defined as cities with a population of less than 35,000 residents, only the quarter-mile area of the TOD zone is covered. And if a county becomes an urban transit county after January 1, 2026, only heavy rail, light rail, and eligible commuter rail will be covered—not BRT.

🤓☝️ Ahem! While airport people movers are not covered, it remains unclear whether the Disneyland monorail is covered.

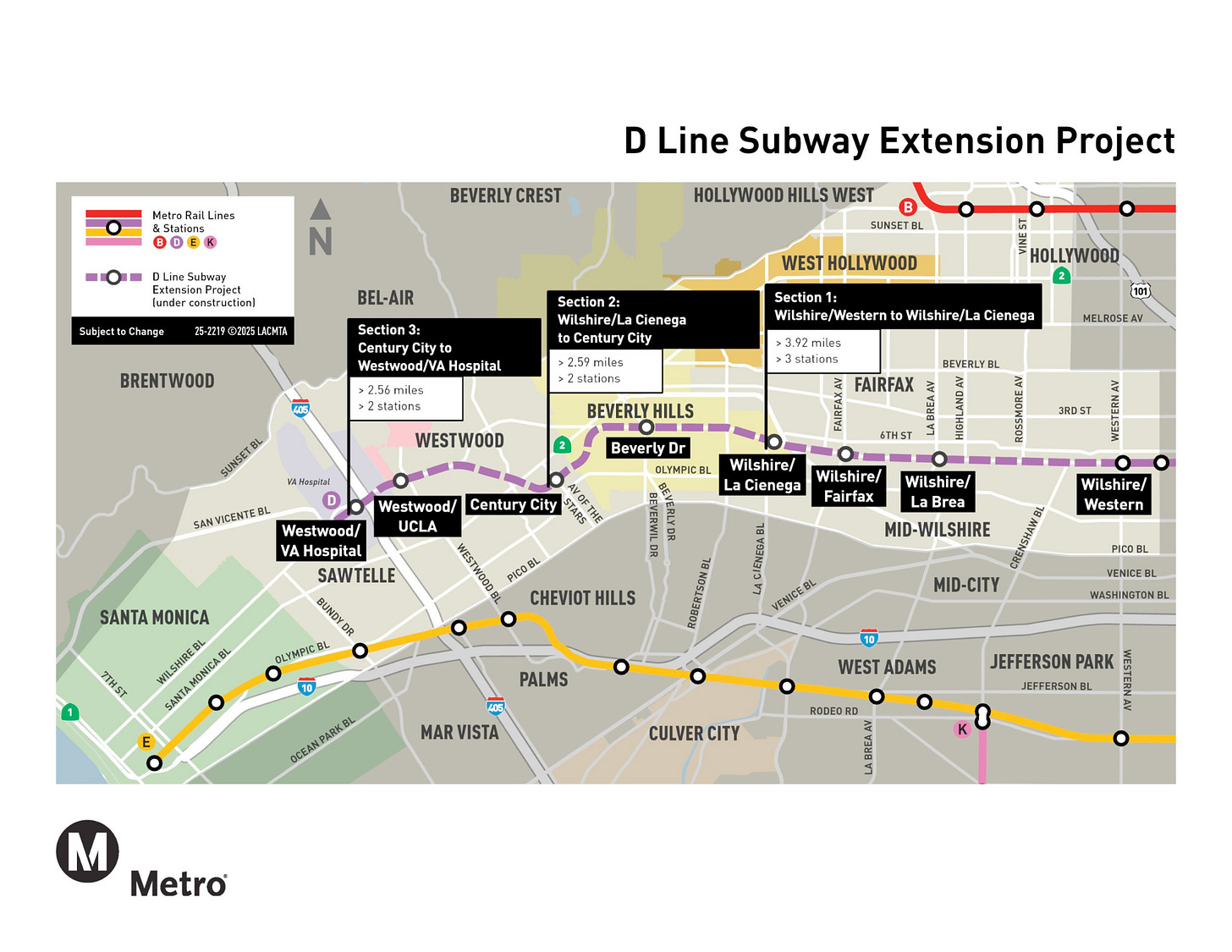

Does SB 79 cover planned stations?

Yes, for the most part. If a heavy rail, light rail, BRT station, and/or an eligible commuter rail station is (a) identified in a regional transportation improvement program, i.e., a funding plan, or (b) there is a locally preferred route, it’s covered.

That is to say, a politician or planner can’t merely float the idea of a station and have it trigger SB 79. There needs to be a real commitment to building out the station, and it has to be reasonably settled where the station is going to be.

Any eligible station planned as of January 1, 2026, will be covered. However, light rail, BRT, and high-frequency commuter rail stations planned after this date will not be covered until they are built out. By contrast, heavy rail and extremely high-frequency commuter rail station areas will be covered once they are planned. (Are you confused yet? As you can probably guess, horses were traded!)

Do you all have a map of where SB 79 upzones?

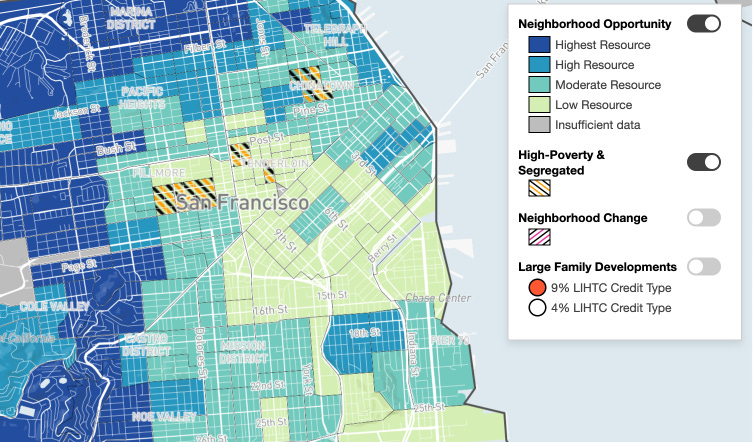

Metropolitan planning organizations are required to produce official maps in the coming months. In the meantime, here’s our best guess at coverage. You should not use this map to make any major decisions.2 We are almost certainly missing some eligible planned stations, and interpretation decisions made by local and state regulators will likely shift coverage on the margins.

🤓☝️ Ahem! Why not share a map sooner? A few reasons: First, the law was in a constant state of flux. In most of the 15 (!) rounds of amendments, the geography changed. Second, we wanted to avoid imperfect maps driving the conversation. Third, various unofficial maps had already been put out by activists.

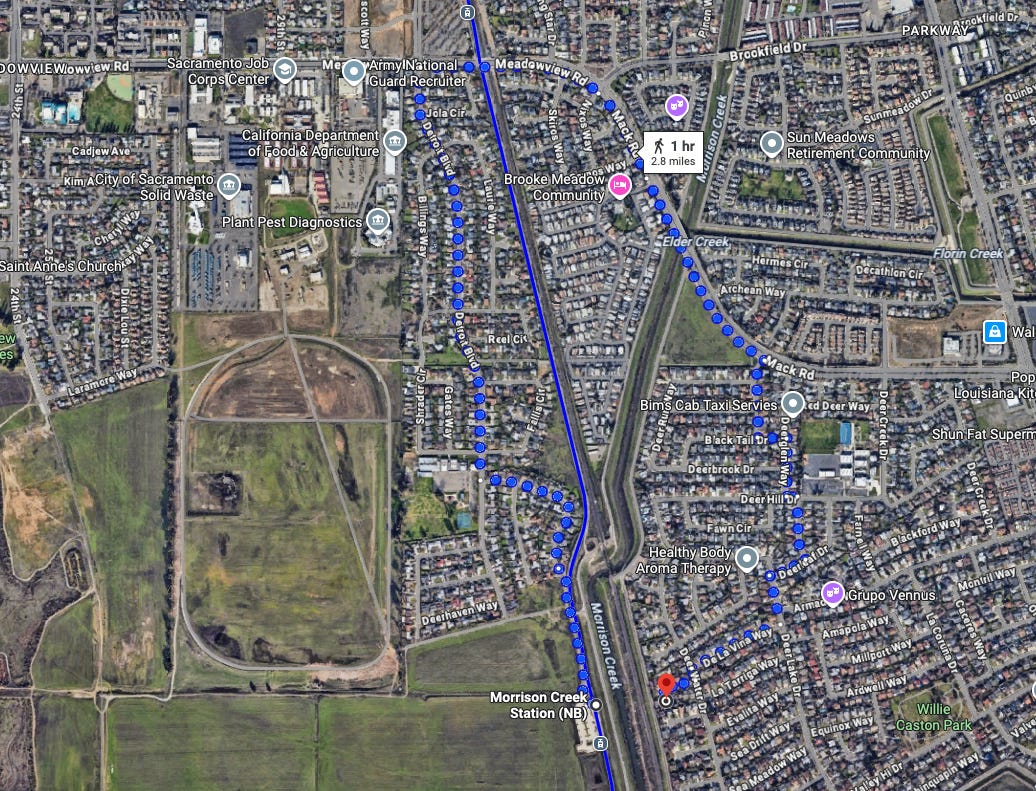

Does SB 79 apply to all lots?

The law applies to all lots that allow residential, commercial, or mixed-use development. Cities can exclude certain lots:

If there is no path from a site to the relevant stop that is less than one mile. For example, lots on the other end of a ravine or river from a station are probably not covered.3

If the station area is part of over 250 contiguous acres of industrial land—and the city has more than 15 eligible stations—the city can designate it as an industrial hub and exclude it from SB 79. For example, Los Angeles will not need to allow SB 79 projects in the heart of industrial South Los Angeles.

Until one year into the seventh RHNA cycle—generally around 2030 for California’s larger metropolises—cities can exclude the following sites:

Lots in a very high fire severity zone.

Lots at risk of a one-foot rise in sea level.

Lots with a designated historic resource.

The following sites:

A site in a station area where the local zoning already allows 50% of the units and floor area that would have been allowed by SB 79.

Why? To defer to recent good-faith sixth-cycle rezonings.

A site in a station area where the local zoning allows 33% the sites to achieve 50% of the units and floor area that SB 79 would have allowed, as long as the TOD area collectively achieves 75% of the units and floor area that SB 79 would have allowed.

A site in a station area that is mostly designated as low-resource by the state treasurer’s office, and where the local zoning cumulatively allows 40% of the density and floor area that SB 79 would have allowed.

Why? To give the most marginalized areas extra time before implementation takes effect.

A site is designated in a low-resource area as long as the city collectively allows 50% of the units and floor area that SB 79 would have allowed across all TOD areas.

A site is covered by a local alternative plan—more on that below.

In all cases, cities must adopt an ordinance declaring that they are excluding any of these sites. They are not required to exclude these sites if (a) they are otherwise covered by SB 79 and (b) local conditions make sense.

SB 79 will not apply to any unincorporated sites prior to the seventh RHNA cycle—no ordinance necessary. In plain English, these are sites that are not incorporated into any city. Instead, they are governed by counties. There’s very little overlap here, as most unincorporated land is rural. But a few exceptional and sensitive sites—namely, unincorporated East Los Angeles—motivated this exclusion.

🤓☝️ Ahem! Contrary to what your crazy uncle may have sent you over WhatsApp, not one square inch of the Pacific Palisades or Altadena is covered by SB 79. Indeed, the point of SB 79 is to allow more housing in climate-resilient infill areas.

Alright, so what does SB 79 allow?

The bill allows mid-rise multifamily housing in all TOD zones. The density and scale of these projects vary based on the quality and proximity of the nearby transit station.

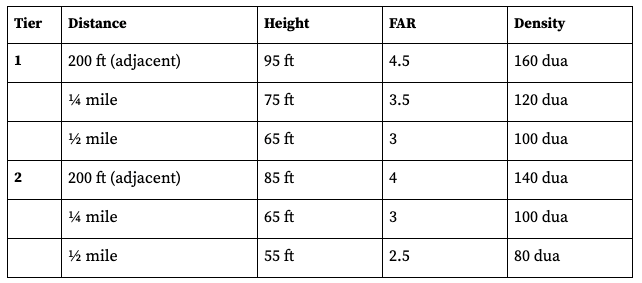

In Tier 1 station areas…

Within a quarter mile of the station…

Cities must allow buildings with a height of 75 feet, a floor area ratio (FAR) of 3.5, and a density of 120 dwelling units per acre.

Within a half mile of the station…

Cities must allow buildings with a height of 65 feet, an FAR of 3, and a density of 100 dwelling units per acre.

In Tier 2 station areas…

Within a quarter mile of the station…

Cities must allow buildings with a height of 65 feet, an FAR of 3, and a density of 100 dwelling units per acre.

Within a half-mile of the station…

Cities must allow buildings with a height of 55 feet, an FAR of 2.5, and a density of 80 dwelling units per acre.

While cities have substantial flexibility to regulate the form and design of these buildings—such as by requiring courtyards or a Spanish Colonial design—they cannot impose any set of standards that collectively make developments built to these minimum standards physically infeasible.

🤓☝️ Ahem! SB 79 defines residential FAR as the ratio of net habitable floor area to the total lot size. No more funny business, Los Angeles!

If a site is adjacent to a transit station—defined as within 200 feet of the station—cities are obliged to allow 20 feet of additional height, increase the FAR by 1, and permit an additional 40 dwelling units per acre.

Here’s a handy chart for the shaperotators in the audience.

🤓☝️ Ahem! All distances are determined based on the nearest pedestrian access point to the transit station. This will be a tricky mapping challenge!

Are SB 79 projects entitled to ministerial review?

No. Which is a bummer—ministerial approvals bring the highest possible degree of certainty to the permitting process. However, a few things are worth noting here:

Given all the work we’ve done to beef up the Housing Accountability Act (HAA) in recent years, cities have far fewer opportunities to arbitrarily deny even discretionary housing projects.

Now that infill housing development is mostly exempt from environmental reviews, the opportunity for NIMBYs to endlessly delay discretionary approvals with litigation is significantly constrained.

Applicants can still use provisions from SB 423—another Senator Wiener-authored, California YIMBY-sponsored bill—to secure ministerial, streamlined approvals.

SB 79 gives state regulators—specifically, the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) and the Attorney General’s office—the right to take actions when cities violate SB 79. If you think a city has violated SB 79 or a project has been inappropriately denied, report it.

🤓☝️ Ahem! Beginning in 2027, if a city denies an SB 79 development proposal in a high-resource area, they are presumed—by default—to be in violation of the HAA and are immediately liable for penalties.

Are there labor standards for SB 79 projects?

Consistent with AB 130—the budget bill that exempted infill housing developments from CEQA—all SB 79 projects over 85 feet must use a “skilled and trained” workforce.4 In practice, this will require an agreement with a union. This is a much more flexible (and feasible) standard than what has been written into recent California housing laws.

Any SB 79 project on transit agency-owned land must adhere to SB 423 labor standards. This is already the norm with e.g., BART-owned land. In all cases, projects must adhere to local labor standards. These are fairly common in the Bay Area and Greater Los Angeles.

Any portion of an SB 79 project that includes a hotel or motel is not entitled to HAA protections.

If successful, SB 79 will kick off a building boom that will create a lot of new construction jobs and bid up the wages of workers. In the meantime, we look forward to working with the carpenters and building trades on bills to legalize high-rise residential developments around downtown transit hubs—projects well-suited to create good union construction jobs.

Are there below-market-rate affordability requirements for SB 79 projects?

SB 79 projects that have more than 10 units must include at least some below-market-rate units. We use the standards set out in AB 1893, which are similarly much more flexible (and feasible) than what has been written into many recent housing laws. Projects must set aside:

7% of units as extremely low-income housing, defined as 30% or less of the area median income (AMI); or

10% of units as very low-income housing, defined as 30 to 50% of the AMI; or

13% of units as low-income housing, defined as 50 to 80% of the AMI.

SB 79 projects must also adhere to local inclusionary zoning requirements, where they are in force.

🤓☝️ Ahem! Cities cannot impose any requirement—whether it be an inclusionary zoning requirement, an additional fee, or some other arbitrary constraint—that only applies to SB 79 projects. Such requirements must be broadly applicable.

In practice, many projects will likely combine SB 79 with state density bonus law, providing additional affordable housing in exchange for additional incentives and concessions. Any SB 79 project that achieves at least 75% of the permitted density is entitled to additional incentives and concessions based on the type of below-market units that it includes. They include:

Three additional incentives and/or concessions for developments providing extremely low-income housing.

Two additional incentives and/or concessions for developments providing very low-income housing.

One additional incentive and/or concession for developments providing low-income housing.

🤓☝️ Ahem! Cities are not obliged to allow taller buildings than the heights specified above, even if additional height is requested as an extra incentive and/or concession. Of course, they can always allow heights above what SB 79 allows.

If successful, SB 79 will help to drive down costs by increasing the supply of housing. (The evidence here is clear and overwhelming.) In future sessions, we look forward to passing bills to defray the costs that unfunded inclusionary zoning requirements impose upon projects—and make more mixed-income projects pencil.

Is there a minimum density for SB 79 projects?

SB 79 projects must include at least five units and achieve a density of at least 30 dwelling units per acre.

Are there anti-displacement standards for SB 79 projects?

An SB 79 development proposal cannot involve the demolition of any existing multifamily building that is subject to any form of rent control or stabilization if (a) the building contains more than two units and (b) has been occupied at any point in the past seven years. In cases where a rent-controlled or stabilized unit is redeveloped, the tenants are entitled to protections set out in the HAA.

Speaking frankly, this area of the law is a mess—there are now a dozen or so different anti-displacement standards in state housing law. State oversight is limited, and tenants often do not receive everything that is entitled to them by the law. The bad news is that SB 79 invents yet another displacement standard. The good news is that it is much more flexible (and feasible) than previous standards.

In future sessions, we would like to work with partners to (a) beef up relocation and reimbursement support for affected tenants while (b) phasing out the flat prohibition on redevelopment that is common across state law.

Can cities implement alternative plans?

SB 79 makes life easy for cities. Unlike RHNA, cities don’t need to adopt any plan. As long as they allow projects that meet the criteria detailed above, they are golden. However, many cities may want to move the density around to suit local conditions. The bill allows cities to do that using a transit-oriented development alternative plan.

Since that’s a bit of a clumsy term, we’ve been calling these Eckhouse Plans. An Eckhouse Plan is subject to a list of rules:

It must allow the same amount of density and floor area that SB 79 would have across all TOD station areas in a city.

It must allow for at least 50% of what SB 79 would have allowed in each TOD station area.

On any given site:

Cities must allow a minimum density on all sites in the TOD station area:

In Tier 1 station areas, the plan must allow at least 50% of the density and floor area that SB 79 would have allowed—that is to say, a density of 60 dwelling units per acre and an FAR of 1.75 within a quarter mile, and a density of 50 dwelling units per acre and an FAR of 1.5 within a half mile.

In Tier 2 station areas, the plan must allow for developments of at least 30 dwelling units per acre and an FAR of 1 on every site in the station area.

However, cities can zero out—and reallocate—density on the following lots:

Lots in a very high fire severity zone.

Lots at risk of a one-foot rise in sea level.

Lots with a designated historic resource designated prior to January 1, 2025, as long as such designations don’t serve to exclude more than 10% of any given TOD zone.

As long as they adhere to these rules, cities have a lot of flexibility to use Eckhouse Plans to move density around—both within and across TOD station areas.

🤓☝️ Ahem! In reallocating density and floor area, cities cannot take credit for an increase of more than 200% on any given site. That is to say, cities cannot zero out the entire station area and allocate all of the density onto a single site.

Notably, these plans are subject to HCD review. Through the remainder of the sixth cycle, they can be adopted via ordinance, and HCD review is optional—as with any other SB 79 implementing ordinance. But beginning with the seventh cycle, these plans must be adopted via housing element amendments, and HCD approval is required.

🤓☝️ Ahem! It will be important for local YIMBY activists to get involved in the development of Eckhouse Plans. In the coming weeks, California YIMBY will be releasing an implementation guide for pro-housing local officials and planners.

How can transit agencies use SB 79?

One of the big objectives of SB 79 was not only to build a lot of new housing, but to help keep California’s transit agencies afloat. Of course, building a lot of new housing near transit stations will help with that, to the extent it will increase ridership.

But SB 79 goes a step further, empowering transit agencies to build on land they own. In the rest of the developed world, collecting land rents on transit agency-owned land—a form of land value capture—is a key source of revenue for transit agencies. SB 79 imports that international best practice into California. If implemented, it could generate billions of dollars in new revenue.

SB 79 empowers transit agencies to build more housing on the land they own. Here are the details:

Eligible sites must either be adjacent to an SB 79 station, or within a half mile of such a station and in the agency’s possession prior to January 1, 2026.

The transit agency must establish the zoning rules for these sites. They must allow at least as much as what is allowed by SB 79, but they can not allow more than 200% of what SB 79 allows.

At least 50% of the development must be comprised of housing.

Developments on transit agency-owned land face additional hurdles. These include:

At least 20% of the units must be deed-restricted at rents affordable to lower-income households.

Transit agencies must host a public hearing and consult with local governments in setting land-use standards on their land.

Transit agencies must also complete an environmental review, for which they are the lead agency.

🤓☝️ Ahem! Something like this was adopted specifically for BART in 2018—AB 2923, colloquially known as the “BART upzoning bill.” SB 79 extends elements of this bill to all transit agencies in California.

When does SB 79 take effect?

The first phase of SB 79 takes effect on July 1, 2026. As detailed throughout this post, some additional measures do not take effect until January 1, 2027. And the full scope of the law does not take effect until a metropolitan area starts the seventh RHNA cycle.

Where can I learn more?

As mentioned above, upcoming posts on this blog will unpack the evolving politics around housing policy in California and explore where YIMBYism goes from here. (Spoiler: we need to focus on cost reductions!) Over on the California YIMBY website, we will soon be publishing a series of detailed guides on SB 79.

If you’re a local elected official, city planner, or state regulator curious to learn more about how you get the most out of SB 79 via implementation, email Aaron Eckhouse. If you’re a developer curious to learn more about what you might be able to build using SB 79, email Muhammad Alameldin. And if you’re an activist interested in getting involved, email Maiya De La Rosa. Operators are standing by!

More broadly, stay plugged in with California YIMBY. Our fight is far from over. We don’t have power in Sacramento because we have deep pockets or long-standing connections. We have power in Sacramento because we have good policy ideas and a grassroots, statewide movement that backs us up. Find out how you can get more involved here. To support our work financially, click here. ❤️

P.S. The California YIMBY Victory Party is coming up. See you there?

We use “TOD zone,” “TOD area,” and “station area” interchangeably to refer to the buffer around any given SB 79-eligible station.

This map does not reflect anyone’s belief as to where SB 79 except our own—among the co-sponsors, we had spirited debates as to what is and is not covered.

We use “site” and “lot” interchangeably, even if the distinction matters a lot to state housing law.

We use quotations not to diminish it, but to clarify that we are using a technical term defined in state housing law.

Thanks Nolan for such a detailed and informative summary!

Fantastic explainer of a monumental piece of legislation. Congrats to all involved, and to the people of California who will now have more affordable transit accessible housing!