How Proposition 13 Broke California Housing Politics

It’s not what you think.

For thousands of years, philosophers have puzzled over what it means to “know” something. Work with me here—there’s a payoff. The traditional understanding goes something like this:

You have to believe it.

It has to be true.

You have to be justified in your belief.

This was all well and good until 1963, when the philosopher Edmund Gettier outlined a counter-example in a three-page paper. Academia really did used to be like that.

Smith and Jones are applying for the same job.

The boss tells Smith that Jones will get the job.

Smith knows that Jones has 10 coins in his pocket, which was the style at the time.

Smith thus acquires the following justified true belief: “The man with 10 coins in his pocket will get the job.”

Eventually, Smith got the job—but as it happens, he had 10 coins in his own pocket.

What’s the problem here?

Smith believed the proposition.

The proposition was true.

Smith was justified in believing it.

And yet, his justification was wrong—he was correct only by accident.

In such a case, it doesn’t make sense to characterize Smith as knowing the proposition, even though he otherwise satisfies the criteria of knowledge. These are called Gettier problems.

I believe that the prevailing wisdom that “Proposition 13 has been a key driver of the California housing crisis” faces a similar sort of Gettier problem. Many people believe it, it’s true, and they have some justification. The trouble is, their justification is wrong.

Wait, what is Proposition 13? Passed by ballot initiative in 1978, Proposition 13 capped property tax rates at 1% of a property’s assessed value, and limited annual increases in assessed values to 2%. A property can only be fully reassessed when it is sold or undergoes redevelopment.

The usual story goes like this: Proposition 13 capped property taxes, making housing a “bad deal” for cities, in that new homes would consume more in services than they pay in taxes. This is all doubly true of apartments that house poor families with children—the ultimate fiscal nuisance. California cities thus rationally refuse to allow housing, and that’s why we have a housing shortage.

QED. Unless..?

Elements of this story are clearly true. In the immediate aftermath of Proposition 13, local revenues collapsed, and housing undoubtedly became less fiscally enticing. Conversely, commercial uses have become more attractive to the bean counters, as they also generate sales taxes. This explains many California land-use oddities, such as car dealerships next to billion-dollar transit lines.1

The trouble is, the basic assumption this story makes about housing—that market-rate apartments are a fiscal net loser—is plainly untrue in 2025. Three crucial changes have inverted nearly all of the received “wisdom” about how fiscal incentives shape permitting in California:

First, Proposition 13 provides a huge fiscal return to redevelopment, especially where a big, new apartment building is concerned.

Second, the changing composition of families in market-rate apartments means that they are less of a fiscal burden than ever.

Third, California’s mind-bogglingly high impact fees more than offset any alleged losses from Proposition 13.

Let’s run through each in turn.

Under Proposition 13, a property tax bill only resets when a property is sold or redeveloped. The longer a property sits still, the more of a fiscal burden it imposes on the city—consuming the same services, while producing less tax revenue. This is why California’s property tax system is so inequitable, with families in identical homes variously paying either $2,000 or $40,000 a year based on when they bought their home.

As a result, a pure homo economicus city manager under Proposition 13 should be doing everything in her power to encourage properties to change hands as often as possible, ideally as part of a larger redevelopment—not blocking housing, as is so often assumed.2 This incentive only increases with each passing year, as the stock of properties underpaying steadily accumulates.3 We’re approaching year 50, by the way.

This appraisal reset provision means that every new market-rate apartment building is effectively a giant pile of free money for California cities. Take a typical five-over-one development near my home in West Los Angeles: 1855 Westwood Boulevard. It turned an old auto body shop into 60 apartments on a 15,000-square-foot lot. How did the annual property tax bill change?

It’s surprisingly hard to find historical public property tax data. But based on “comps” on this corridor—i.e. other low-rise 15,000 square-foot commercial lots—the auto body shop likely paid around $7,400 per year. This new apartment building pays $93,621 per year. That’s an increase of $86,221 per year—enough to pay a civil servant’s salary—or $862,210 in additional public revenue over a decade.

“Okay,” I hear you say, “that’s a lot of money. But aren’t all these people consuming more public services?” Maybe so, but this is where another change that has happened since 1978 comes into the picture: people who live in market-rate apartments in California are pretty well off these days, and households in general—but especially those in apartments—are a lot less likely to have kids.

Let’s return to 1855 Westwood. The typical one-bedroom apartment rents for $3,730. You would need to earn $135,636 to comfortably qualify for one of this unit. That’s not the profile of someone who is going to place a huge burden on public coffers.4 On the contrary, they are going to spend a lot of money and generate a lot of local sales tax revenue—money that is ignored when calculating the fiscal impact of new housing.

And about those pesky children: Nearly two-thirds of this particular building consists of one-bedroom and two-bedroom-two-bathroom units, all of which will be filled by single young professionals or couples, perhaps with a baby or two. There’s a decent chance there isn’t a single school-aged child living in this building. And even if there are two or three few kids, Los Angeles public school enrollment has plummeted in recent years—I’m confident we can find space for them.

Again, this building is free money for Los Angeles. If we wanted to avoid the city’s impending fiscal collapse, we would build many thousands more buildings like this. According to a preliminary analysis by Streets for All—the full report is coming out soon—Los Angeles could turn a $931,000,000 budget deficit into a $349,737,846 budget surplus simply by allowing for more apartment buildings near transit.5

The claim that apartments are a net fiscal loser under Proposition 13 becomes even more absurd when you consider the fact that California now imposes some of the highest impact fees in the nation. Unique among U.S. states, building housing in California requires that you fork over tens of thousands of dollars before you can even get a shovel in the ground.6

The legal fig leaf underwriting these fees is that they fund the “impacts” of new housing, but it’s an open secret that they are treated like general revenue.

Assume 1855 Westwood paid an average amount in terms of per unit impact fees, or $37,471. With 60 units in the building, that means the developer—or in a Coasian sense, Los Angeles renters writ large—paid a total impact fee bill of $2,248,260. And that’s before accounting for the many tens of thousands of dollars in “user fees” the developer must pay for entitlements, permits, and utility hookups, which are invariably padded out to generate revenue.

Let’s pause to take stock: A net gain of $86,221 in annual property taxes. Minimal new public service demands. A flood of new sales tax revenue. An upfront lump sum of $2,248,260. How catastrophically misgoverned would Los Angeles need to be for this development to be a fiscal net loser?

Taken on its own terms, the classic theory of how Proposition 13 drove the California housing crisis was never really backed up by the data.

In the 1980s, the fiscal disincentive for redevelopment was strongest. There wasn’t yet a big windfall associated with the reassessment triggered by redevelopment, and impact fees were low and uncommon. And yet, California went on a building boom.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and the potential bump in public revenues from redevelopment is real. You had a lot of properties that are bleeding cities dry with 40-year-old appraisals, and impact fees are high and widespread. And yet, housing permitting rarely has rarely cracked three units per 1,000 residents in recent years.7

Can we finally put this theory to bed?

🌴🌴🌴

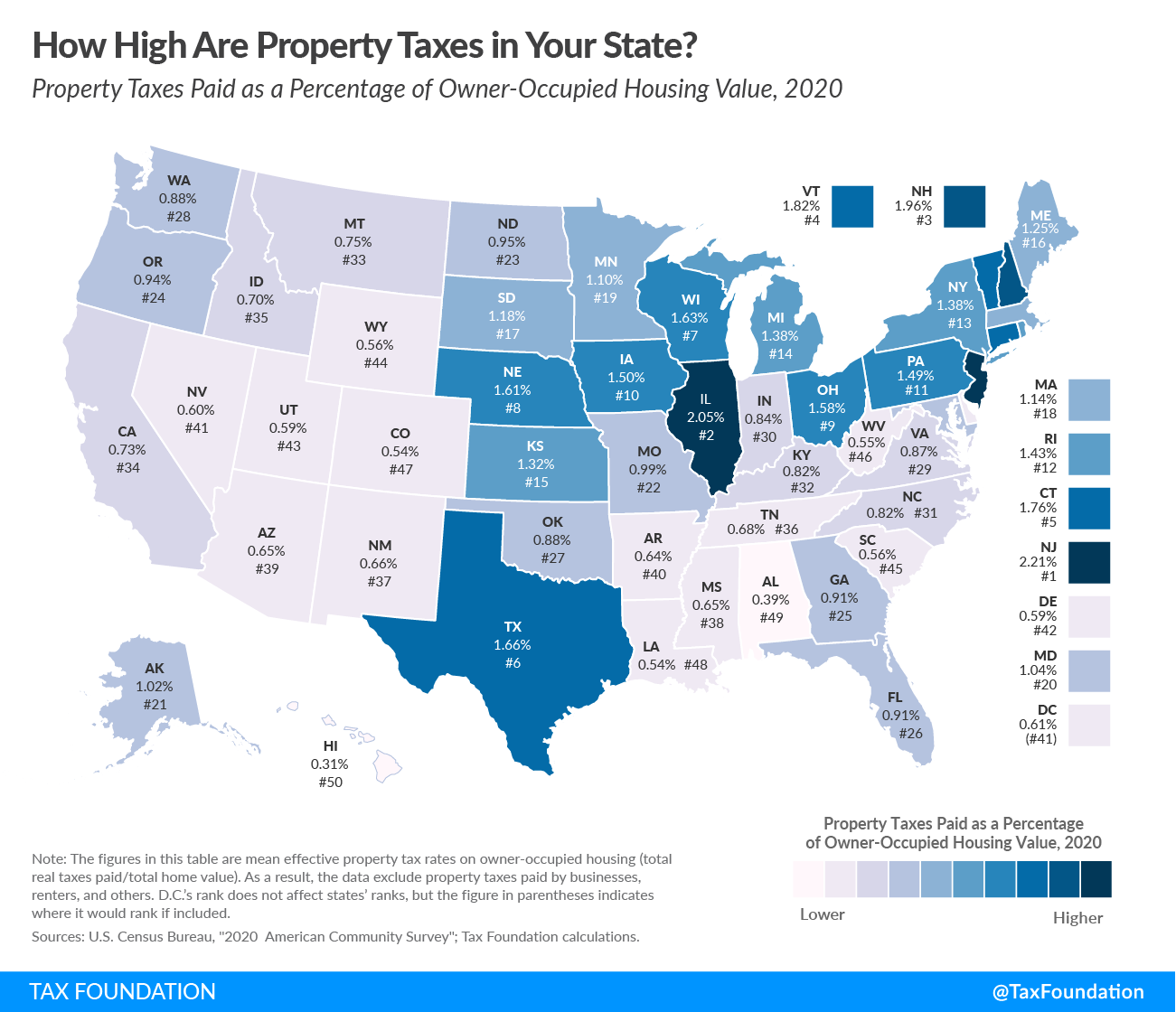

As the title of this post suggests, I do think Proposition 13 has been a key driver of the California housing crisis. Even a passing glance at a state-level property tax map makes it clear that states with higher local property taxes are more pro-growth than their peer states, all else equal. But if it’s not about net fiscal winners and losers, what’s it about?

Join me for a detour back to normal America. Every year since 2020, I’ve received a message from a friend or family member back home in Lexington, Kentucky newly curious about my work: “So, how do we bring down home prices?” It’s not because their rents went up—on the contrary, they’re virtually all homeowners. Rather, it’s because they got their annual property tax bill, and it kind of freaked them out.

Take a typical home in the neighborhood I grew up in: 976 Deer Crossing Way. At the start of the pandemic, the house was appraised at $215,700. Fast forward five years, and it’s now worth $264,300. Haha, heck yeah! Yes! $48,600 in free wealth! Except, over of this period, our homeowner’s annual property tax bill increased by $349.20.8 Well, this sucks. What the heck?

This homeowner in Kentucky—as in most states—is annually reminded of what’s going on in housing markets, and given a financial incentive to not let prices skyrocket. To restate the case directly: property taxes give homeowners a financial stake in keeping local housing prices under control. It gives them skin in the game for ongoing affordability.

Think of property taxes as a kind of empathy pump, putting incumbent homeowners at least partly in the shoes of prospective future homebuyers. Under a normal property tax regime, a homeowner in must be at least somewhat open to local policies designed to increase the housing supply, if only to keep prices steady. Otherwise, he will be paying a lot more in property taxes each year.

Indeed, a normal property tax system gives the typical homeowner an incentive to support the construction of new apartments—if not next door, at least on nearby corridors and downtown.9 After all, these projects will (a) generate more tax revenue and (b) suppress price increases, both of which will decrease her annual property tax bill. This is especially important if she doesn’t plan to move away anytime soon—the only way to realize the gains of home value appreciation.

Thus, fiscal zoning properly understood doesn’t work by shifting the incentives facing city managers—it works by shifting the incentives facing the people who actually set local policy, which is homeowners.

Compare this to the experience of a typical California homeowner—the sort of person who bought their home for two magic beans and some belly button lint in 1970, and is now the proud owner of a $2 million asset.10 This person has no reason to pay attention to housing costs, let alone any incentive to bring them down. On the contrary, rising home prices are almost purely to their benefit.

Thus, the typical California homeowner has no financial incentive to support policies that might increase the housing supply and create the next generation of homeowners.11

Of course, everyone likes it when their assets go up in value. And in a healthy housing market, homes are a good store of wealth—they nearly always hold their value.12 I don’t buy the whole “homes can’t be an investment and be affordable” line, because (a) there is little variation among U.S. states in terms of whether one can treat a home as an investment, and yet (b) there is a lot of variation among U.S. states in terms of affordability.13

But the dynamic in California—in which incumbent homeowners flat out don’t care about housing costs, and aspiring homeowners leverage themselves to gills in anticipation of jackpot returns—is plainly toxic, and it is enabled by Proposition 13.

Proposition 13 created a situation where, until things got really bad, the average homeowner could stop caring about housing affordability. Only now that the California housing crisis has gotten to be so bad that it hurts even incumbent homeowners—their children and grandchildren moving away, tent encampments sprouting up near their home, their city on the verge of bankruptcy, the cost of everything going up—is meaningful reform finally underway.

When you create a system that makes homeowners—the most powerful interest group in local politics—demand endlessly higher home prices, it turns out that you will get policies that result in endlessly higher home prices, and all the devastation this entails. This is the mess Proposition 13 created.

As other states flirt with imposing arbitrary caps on annual property tax assessments, let California be a warning: You might not like high property taxes. But the only way to sustainably bring them down without destroying your city and state is to build a lot more housing.

By the way: how many coins do you have in your pocket?

Addendum: Why does any of this matter? If your justification for a true belief is wrong, the actions you take based on it are less likely to achieve the desired outcomes.14 If you believe Proposition 13 causes the California housing shortage by making new housing a fiscal loser, you will pursue policies like giving local governments more money in exchange for growth. Now, I tend to think we should give local governments more money—indeed, I’ve floated the idea of restructuring the United States into 100 citystates. If you’re in a position to make this happen, call me.

But if my argument is correct—and the issue with Proposition 13 isn’t really how it changes the net fiscal impacts of new development, but how it changes the incentives facing homeowners—transferring more money to local governments that allow more housing isn’t going to meaningfully change the political economy of this issue. It will help on the margins, to be sure. But as long as housing scarcity is an unalloyed good for incumbent homeowners, the incentives facing local elected officials in setting land-use policy aren’t going to change.

The only sustainable fix is going to be to shift these decisions to a level of government less prone to capture by homeowners—that it to say, state preemption.

American land-use planning is bad, but it isn’t that bad—follow the money.

And if you think the typical city manager is really gaming out property taxes 50 years down the road—to say nothing of politicians operating on a four-year election cycle—I have a bridge to sell you.

Will a generation of subsidized homeowners pass away and solve this problem? No. Proposition 13 tax assessments can be inherited by heirs. Before you ask, yes: America’s most progressive state created a class of untaxed hereditary landowners.

What public services will this person consume? The roads and sidewalks they use exist either way, as do the parks. Will the marginal use of libraries or community centers trigger substantial new liabilities? I find that hard to believe. This is why infill development is such a good deal fiscally for cities, as urban planner Joe Minicozzi repeatedly points out: it leverages existing infrastructure and services. (It would be wrong to write a post about how a lot of inherited fiscal zoning “knowledge” is junk without mentioning him.)

I would note that cities in New Jersey seem to understand this—all up and down the Northeast corridor, you can see otherwise exclusionary commuter suburbs tossing up apartment towers next to stations. Why? It’s free money: a tower of studios and one-bedrooms for singles commuting into New York City every day produces an avalanche of new revenue, with basically no new public service obligations.

Historically, capital expenses required by new housing were paid for with bonds that were gradually paid down by the community as a whole through property taxes. If you live in a home built before the 1970s in California, or a home built at any point in much of the rest of the U.S, this is how all the infrastructure you enjoy was financed. This is a much more equitable way of financing such work, recognizing that there is a shared interest in ensuring that new housing gets built. No such social ethos informs modern California.

“Classic” fiscal zoning theory isn’t borne out in California on various other margins. For example, if net fiscal impact is the overriding concern in permitting, why have cities like Los Angeles so aggressively prioritized the construction of subsidized, deed-restricted low-income housing?

Worse yet, this annual increase will be paid each year, while the hypothetical increase in home value can’t be realized until the homeowner sells and moves away, which could be decades in the future.

This incentive may not always win out over quality of life concerns, unstated class- or race-based animosities, or an unsophisticated opposition to change—but it at least pushes things in the right direction.

If you really want to be cruel, ask a longstanding homeowner in California—perhaps a NIMBY politician—what he thinks the median home price is in his area, and prepare for the most cartoonishly low estimates. Conversely, I find that friends and family in suburban Kentucky can reliably offer up a pretty solid guess as to the home prices on their block.

In an important sense, it’s the same sort of “I got mine” philosophy that underwrites impact fees.

Single-family home prices basically only ever collapse in value in real terms as a result of a local economic collapse—e.g, a factory closing. The nice thing about prices is that they equilibrate.

On the contrary, cities and states that have undertaken efforts to limit investor activity—such as cracking down on institutional investors, foreign buyers, vacant units, and short-term rentals—are invariably the most unaffordable places. This can’t all be written off as endogeneity. I may return to this issue in a future post.

Too many people read the Stoics, and not enough people read the Pragmatists.

I always assumed the causal method of prop 13 → Minimal redevelopment was much simpler:

Individual homeowners who are not leaving the state and have lived there during widespread appreciation have a huge incentive to stay in the same home: the cheap property taxes they lose if they are to move.

Take for example someone who owns a $2.2 million dollar single family home next to a transit station. They pay $2k per year in property tax, while neighbors across the street pay $22k per year. Selling their home and buying the home across the street costs them $20k per year, even if there are zero real estate transaction costs and the prices of the two homes are the same. It follows that this $20k/year reduced living expenses has value to them, and they will not sell for less than an additional amount (let’s say an additional $500k, though it could be easily another $1M for someone in a high tax bracket) over market price as a single family home.

This raises the implicit price of land (especially when trying to amass multiple parcels) by an increasing amount as long as the average tenure of homeowners gets longer. That in turn raises rents necessary for new redevelopment to happen. Ergo, less redevelopment because of land availability being lower than peer states, not because of some large difference in land policy allowing more redevelopment elsewhere.

This causal hypothesis also conveniently explains longer commutes and higher VMT: when switching jobs, homeowners do not want to move because of the additional ‘forfeited prop 13 benefits’ when they sell one home and buy another.

Would love to see some data on whether changes in land policy are actually more common in peer states versus California, or if the land cost for redevelopment projects is a bigger factor.

Well-put. I agree that the real operating mechanism of Prop 13 is that CA homeowners become insulated from the pain of out-of-control home price growth. (Wonder if there's a category of yearly or monthly expenses like prop tax -- e.g., car insurance -- that feel to consumers like they should be constant, such that any increase prompts an outsized reaction.)

But I'd like to offer up one small anecdote to show how this dynamic can also stymie new home construction.

My family was in the business of mixed-use development in Texas (buying distressed properties like abandoned factories in CBD-adjacent warehouse districts and redeveloping them into downtown apartments plus commercial space). I'll never forget attending a local homeowner meeting one evening, as we were presenting a project update along with city officials, and concerned homeowners kept objecting to the idea of redeveloping this abandoned factory in the first place. "But this is such as 'win' - bringing jobs and new apartments to this part of the city, that everyone agrees has been historically disinvested from!" we argued. But no. The big applause line of that from the homeowners' side was, "But if this project succeeds, our taxes will go up! Many of us are on fixed incomes. We don't want this!"

Zooming out, the idea of local control and granting homeowner's veto to projects benefiting the entire area was such a mistake.