Your City Shouldn’t Exist

And neither should mine.

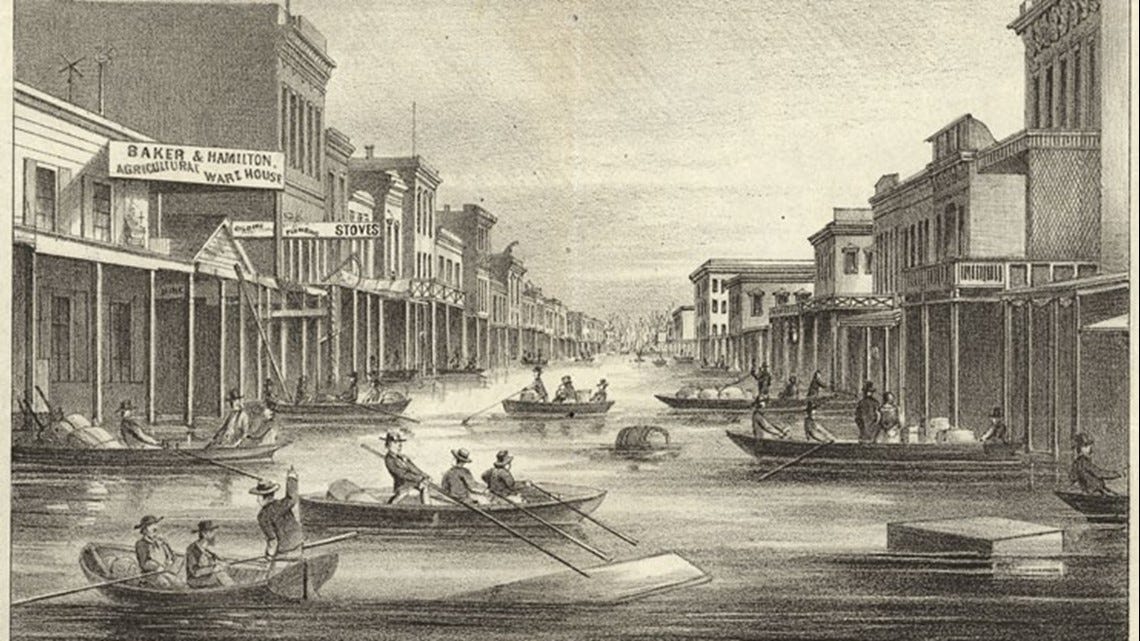

Since moving to Sacramento in April, I’ve made a point of reading various local histories. The early history of the city is brutal: As soon as it was founded, the “Great Inundation” of 1849-50 ravaged the city, as did smaller floods on an annual basis. And then the Great Flood of 1862 nearly wiped it off the map.

In response, Sacramento’s scrappy founding generation elevated the city by 12 feet and built a network of levees and canals. But why build a city here at all? The area that comprises modern Sacramento is a kind of seasonal sea, periodically flooding every few years amid torrential downpours and the Sierra Nevada snowpack melt. If a city needed to exist here, it should have been on a hill a few miles south.1

It’s the same “original sin” story I encountered when I first moved to Los Angeles. Crack open any Southern California history, and you’ll find a self-satisfied list of reasons why America’s second great metropolis shouldn’t exist. It lacks a local source of water. It lacks a deep water port. It isn’t a natural junction. It’s riven by earthquakes. And by the way, did you know it's a desert?2

Read this under clear blue skies on a typical 70-degree day, a palm tree swaying in the distance, and it should be obvious why the city exists. Blessed with a perfect Mediterranean climate and hemmed in by beaches and snow-capped mountains, the coastal plain that hosts modern Los Angeles is an Earthly paradise.

Of course, Los Angeles—like Sacramento—had to be willed into existence. But that’s a trite observation that’s true of nearly every city.

Indeed, no city should exist. The archeological evidence suggests that we as a species only started building cities around 6,000 years ago.3 To put it in “children’s science museum” terms, if the history of humanity is a day, we only started building cities at around 11:30 PM. Cities aren’t our anthills or beehives. We don’t build them out of instinct. There isn’t supposed to be a city anywhere. They exist because we will them into existence.

🌴🌲

For reasons I don’t fully understand, we love to tell these stories about the origins of California cities. Other American cities get the nagging treatment: Bring up your recent trip to Miami or Phoenix, and the smartest person in the room will remind you of how these cities will soon be underwater or out of water, respectively.4

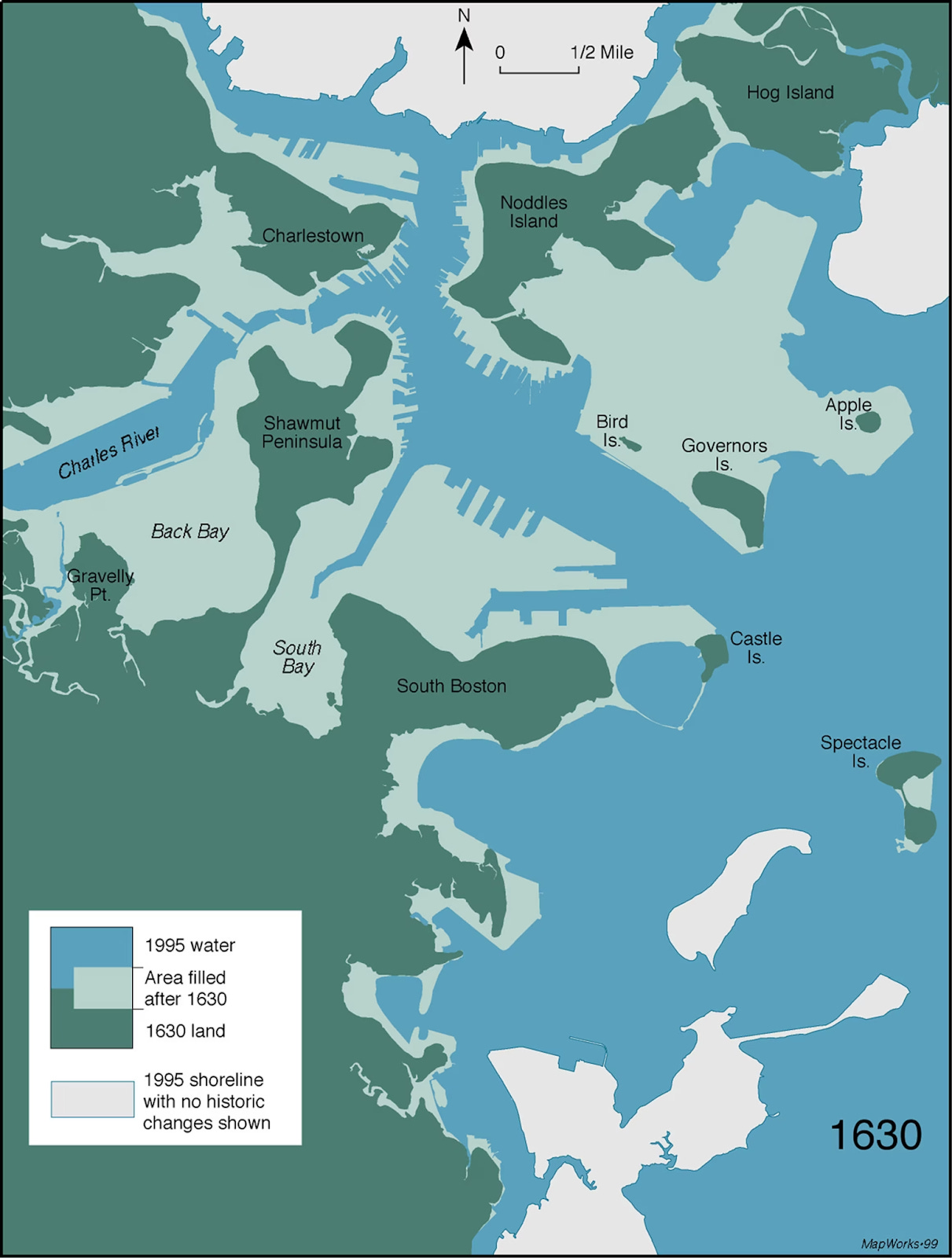

And yet, the same story could be told about most US cities: Half of Boston was dredged up from the ocean. St. Louis only exists because we tamed the greatest river on our continent. Supplying Philadelphia with drinking water is an engineering feat on the scale of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. And much of DC was, infamously, a swamp.5

This trend is hardly unique to North America. Let's take stock of the greatest cities ever built: Tokyo and St. Petersburg required engineering feats on the scale of anything seen in the US. Amsterdam and Mexico City were literally built on top of water. Hong Kong and Rio de Janeiro were carved out of mountains.

Nothing about these cities is natural. Yet once the work is done, we usually adopt a sort of “immaculate conception” view of cities. “Of course, there should be a great world city at the site of Istanbul—it’s the gateway of two great seas!” Never mind that it required the leveling of seven hills, mazes of retaining walls, and many hundreds of acres of land reclamation.

When the work of city building is not yet complete, as in developing cities like Dhaka or Lagos, it disturbs us.6 The comments section of posts about active city building in places like Bengaluru or Shenzhen are sure to be rife with Western disgust. And if a city is ever being built in a desert, such as Dubai or Riyadh, it’s best to just turn off comments from the start.

Yet archeological evidence suggests that early cities first formed in precisely the places that weren’t terribly well suited to permanent human settlement. What we often call the fertile crescent—a stretch of the Middle East characterized by vast deserts and unpredictable river valleys that birthed the first cities—might just as well be called the fragile crescent.7

In a land of milk and honey, cities lack any sort of early modus operandi. But in a world where survival depends on coordination and exchange you need cities.

🌴🌲

Of course, not every city requires extreme terraforming. Take Chicago—nature’s metropolis, as dubbed by historian William Cronon.8 Sitting at the center of what would become America’s industrial and agricultural heartland, there was likely always going to be a great world city here. But did it need to be Chicago? Why couldn’t the capital of the Midwest have been Detroit, Indianapolis, or Milwaukee?

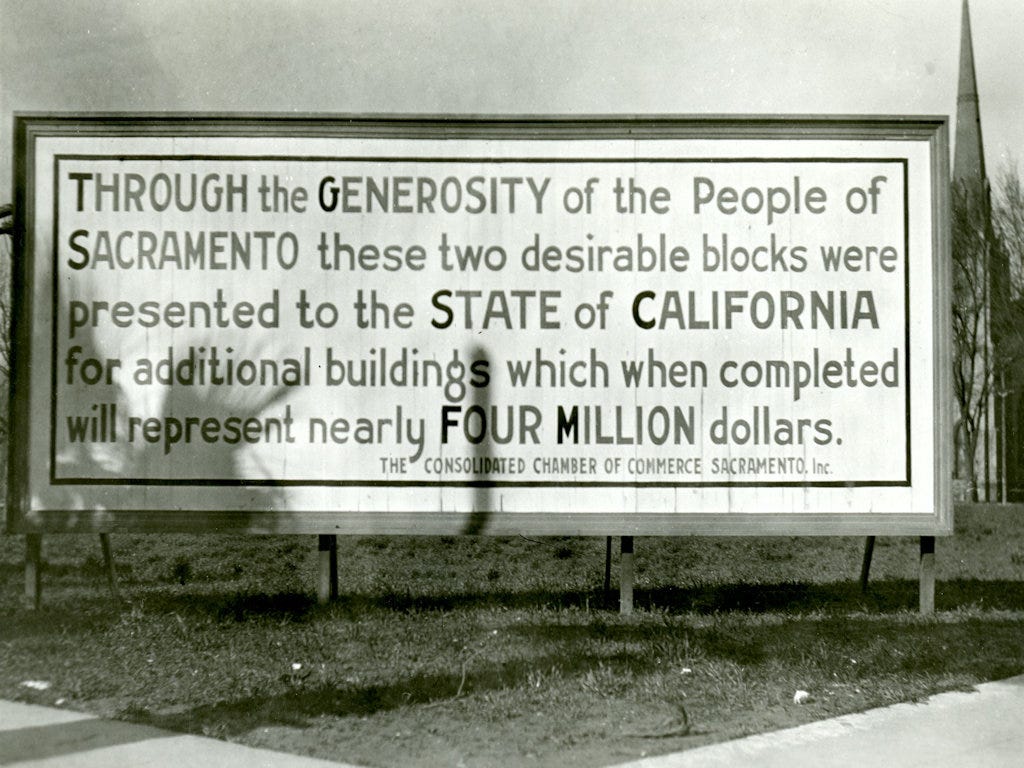

Let’s return to Sacramento, a city I know better: There was likely always going to be a great metropolis at the center of the Central Valley. But Benicia, Marysville, and Stockton all could have served this purpose, as could the dozens of gold mining-era towns that now no longer exist.9 Why did Sacramento become a great city?

I often make fun of contemporary applications of the “urban growth machine” theory. There may be a parallel universe where a desire for growth drives urban politics in America’s superstar cities, but it isn’t the one we live in.

But if you look at the early history of virtually any American city, that’s precisely what’s going on.10 Local coalitions of interests with a financial stake in population growth are competing to attract the recognition, infrastructure, and investment that will put growth on solid footing.11 Thus, all great cities begin.

In the case of Sacramento, that meant (a) securing the state capitol, (b) securing the state fair, and (c) securing the western terminus of the Intercontinental Railroad. Despite all of Sacramento’s shortcomings, and the strengths of all our competitors, we became a great city—and they didn’t—because, at one point, our “urban growth machine” was better organized than theirs.

Similar stories lie at the origins of most great cities. Las Vegas is a major world city because the local tourism industry got organized in the 1930s. Atlanta is the capital of the South because local boosters successfully made it the crossroads of Southern rail. And it’s not obvious that New York City is the great metropolis of the Northeast without the Erie Canal.

For all the focus on “planning,” cities are essentially emergent processes. But we should not lose sight of the fact that equilibria emerge, evolve, and break down as a result of the many millions of experiments being run by place-based entrepreneurs. No city should exist. They exist because specific people, at specific times and places, facing specific constraints continuously will them into existence.

That is, except for Lexington, Kentucky—a city that must exist in all possible universes, for reasons I will go into in a future paywalled post.

Specifically, in the elevated area that is today bisected by Sutterville Road.

Psychedelic infused visions of Atlantis notwithstanding.

The sheer tenacity of New Orleanians—the tragic events of Hurricane Katrina—has afforded them the benefit of the doubt. But say anything nice about Houston, and you will receive an Old Testament sermon about how Houstonians are testing God and will soon be punished.

I learned this from Cities: The First 6,000 Years by Monica L. Smith, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

Indeed, discourse about Chicago has been naturalistic in quality since day one. Just look at the Chicago School, which discusses neighborhood growth and changes the way one might discuss the Darwinian competition for evolutionary niches.

Benicia came quite close to becoming California’s capital.

It strikes me that, “at what point to urban growth machines” politics yield to a prevailing politics of stagnation? In most blue state cities, we know this happened at some point between the 1960s and 1980s. But why? And why did red state cities not follow this trajectory? Better understanding this transition is key to rolling back NIMBY hegemony.

The “growth machine coalition” canonically includes landowners, developers, newspapers, unions, universities, hospitals, as well as the chambers that represent them and the local elected officials who speak on their behalf.

Weren’t almost all great cities located at harbors (or locations with access to a harbor) or on a navigable river prior to railroads? Not that these conditions were sufficient to determine which cities became great, but just that they were necessary. Prior to the invention of railroads, I think it would have been nearly impossible for Atlanta to become a huge city. That is to say, there is a reason why almost all major US cities prior to the US Civil War were on major waterways, and why so many canals were built linking different waterway systems.

"In most blue state cities, we know this happened at some point between the 1960s and 1980s. But why? And why did red state cities not follow this trajectory? Better understanding this transition is key to rolling back NIMBY hegemony."

In "Why Nothing Works," Marc Dunkelman describes two conflicting ideas in progressive politics, which he calls Hamiltonian (the need for big government to counterbalance big corporations and deliver public services) and Jeffersonian (suspicion and mistrust of power, whether private or public). Since the 1960s and 1970s, the balance has swung heavily to the Jeffersonian side, and its suspicion of power (including the power of the government) has been institutionalized in protracted public consultation and judicial review.

Jacob Anbinder describes the origins of anti-growth politics in Democratic cities: skepticism about the preceding period of rapid growth, historic preservation (aiming to stabilize declining neighbourhoods and increase their value), environmentalism, and again, Jeffersonian decentralization. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=njaB0HAnkik

It'd be interesting to see a history of Republican thinking about growth during the same period of time - perhaps a history of Texas.